There are several theories on how RPG’s function and what that may mean. The intention behind my RPG  ludology and having a personal critical theory is practicality. It is handy for writing and during play, and as a framework in the designing of games. This is how I understand roleplaying games as a whole and this helps me not only to run games but also in writing them. This theory seems correct based on personal practice, experience, and observation. In addition, the basis of this hypothesis is the cursory analysis of actual play at the table during contiguous collections of sessions.

ludology and having a personal critical theory is practicality. It is handy for writing and during play, and as a framework in the designing of games. This is how I understand roleplaying games as a whole and this helps me not only to run games but also in writing them. This theory seems correct based on personal practice, experience, and observation. In addition, the basis of this hypothesis is the cursory analysis of actual play at the table during contiguous collections of sessions.

At the core of all RPG sessions is a hierarchy, though more of a stack of information, starting with the most basic component called a Play Unit from which the other higher ordered components arise from accumulation. However, these elements are artificial cross-sectional slices cut from the whole as a means to simplify the study and illustration of it. The entirety of this hierarchy flows and melts together during play. This flow is evident especially when games stall or fizzle out. It is this flow of information that has been interrupted when that happens.

It is this flow of information and the processing and acting upon it thus contributing to it is what not only keeps players immersed in the game but also is the game itself. This two-way flux of information is what is required to deposit the details that create the in-game world in which the Players’ personal blobs of info exist as characters.

One of the easiest ways to explain RPGs is comparing its structures to similar structures in fiction. This aided by the fact that the borrowing of elements between RPGs and fiction is simply uncontroversial. Roleplaying games especially those modeled after genre fiction can be seen as the gamification of fiction. Collective story telling is present in the element of information exchange that lies at the core of all RPGs. Rules structure these elements and introduce gamification into the whole.

Rules set limits; essentially the game mechanics set the diegetic frame and thus may affect multiple aspects of the experience at a very basic level. It is within this perimeter of the rules that the game world both exists and reacts to Player Character (PC) actions. It is also within this framework that the Game-Master (GM) must function in both writing and refereeing.

This flow underlying all RPGs requires the use of more precise but still flexible and understandable terminology. These terms being Diegetic or In-Game and Metagaming or out-of-game which reveals a flow of information between reality and the imaginary world of the game. This flow is filtered and limited by the mechanics of the game where the story-telling elements operate on the structure of a game within the arena of the game-world.

Diegetic (in game) occurs within the context of the game world. Commonly used in terms of cinema, this refers to what exists within the context of the film apart from reality. Its common definition is a form of storytelling/fiction whose narrative presents from an interior point-of-view.

Metagaming/OOG (out-of-game) is comparative to the plot-hole in fiction or even the breaking of the fourth wall. This also comprises of the rule set used in play as well as any structure, elements, or decisions provided by the GM that exceed the limits of the rules. Essentially anything Meta in this context is an element that comes from outside of the diegetic elements of the game, influence from outside of the game universe.

My RPG Session Structure Theory

As tabletop RPG play is built upon the accumulation of information, the exchange and back-and-forth flow of said information is key to how RPGs function. The exchange of information is essential to all RPGs. This includes World Building, Character Actions, and Processing actions and choice through the chosen ruleset. All tabletop RPG game systems require a high level of information exchange. This exchange is dynamic where improvisation occurs naturally within the flow introducing and sometimes spontaneously producing new information or otherwise transforming existing info.

The game begins when the Game-Master (GM) presents some information to the players and allows them to act upon that info from whence the flow of information springs. These exchanges can be the actions and responses of the PCs, Player questions, and/or the responses and text presented by the GM. Each bit of that flow of information, each Play-Unit, is essential in that an accumulation of exchanges is what builds the fantasy world and what institutes player engagement. The players must find some bit of information in these exchanges to latch onto, that is their attention or interest must be piqued by something either contained within or inferred by the Play-Unit thereby engaging them. This is what keeps them participating in the exchange and thus not only going with the flow but producing it.

Therefore, the flow of information is how roleplaying games work but to understand this fully requires us to analyze the exchanged information by looking at it in strictly defined pieces arranged into a hierarchy based on the self-contained complexity.

Play Unit

A Play Unit is the smallest component of RPGs, which is an exchange of information between the GM and a Player or group of Players. Note that Play Units may occur out of sequence as real-world table chatter and meta-gaming discussions counts as Play Units as well possibly obscuring a direct contiguous flow of information. The closest analogy in fiction to a Play Unit is a Story-Beat.

A Story-Beat (from Story by Robert McKee, p.37) is an emotive change in a character or exchange between characters (as in action/reaction) replaced in RPG Narratology with the social exchange between the participants these being the Game-Master (GM) and the Players. Characters that exist within the game are reliant on at least two sources or groups of authors. These are the Player Characters (PCs) controlled by the players and the Non-Player Characters (NPCs) run by the GM. It is between these entities where the story-beats lie. RPG story-beats are smeared across realities. That is, they are present inside of the game world (diegetic) and without among the participants (Meta) in the real world.

In addition, there is not always an emotive change marked in specific characters determined by a single author. These emotional changes in tabletop RPGs is dependent on the exchange of information on what the characters are feeling and doing and how the players themselves are reacting to what is going on within the game (both diegetic and metagaming). Since the emotional change so to speak is distributed over multiple people and existent partially in a shared fiction, it is the exchange of information between these participants and frames of experience (a la Frame Analysis) that is of importance here with each single exchange between participants being a Play Unit.

The way in which the participants understand and give meaning to their experiences is to frame this experience in a finite province of meaning akin to a theater stage contained within the imagination. [Fine, Gary Alan. 2002. Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds. University of Chicago Press. p.181] Play Units not only comprises the flow of information between participants but also accrue to create the stage upon the existent framework of the rules. This stage is the diegetic part of the game and it is linked to the real world via the social interaction of the participants, which exists in the meta-game often blurring the distinction at some junctions but without affecting the participants’ perception of what is real and imaginary.

A Play Unit is produced when there is a single exchange of information between participants that effects or has consequences within the game world. Interaction with only the rules or raw mechanics of the game system does not. The rules are a filter for the raw information working on that information packaging it into a form communicated to the GM and then which the GM works on within the context of those same set of rules and then replies with a similarly packaged bit of information. Thus, the rules or mechanics of a game are a third necessary part of this vital exchange. The rules act as a filter and/or algorithm acting to alter info. This transformation of raw information gives rise to system specific lingo and in-game quirks as side effects unique to a specific rule system.

- Three Vital Parts of a Play Unit are the GM, Players, and Rules/Mechanics

Not all exchanges in a game session are important and are of different levels of importance and immediacy however. Most important exchanges will contain a nugget of info that the GM can play on later, apply directly to the current action in-game, and those that may hint or directly spell-out character traits and especially player interest and reaction. Therefore, it takes multiple limited exchanges transformed by the game mechanics to conglomerate together to create a larger more cohesive unit. These key exchanges are what construct the game world in the minds of all the participants. These key exchanges involve multiple Play Units that build a single fictive scene known as an Episode.

Episode

An Episode is an incomplete part of an adventure where a group of things happen (a large accumulation of Play Units) which seem to be leading to the next episode or a conclusion. Essentially a single incident or short series of incidents occur in some relation to each other. In the world of fiction writing, these are roughly analogous to scenes.

In fiction, a Scene (from Three Genres by Stephen Minot, pg.376) is a unit of action within a story marked by a change of time or place (change of scene) which contains an event that moves the story forward. Note that the entrance of other characters can also demarcate scenes. The same is true of tabletop RPGs save that the demarcation of a scene is more reliant on the change of challenge to the Players such as the presentation of a question, puzzle, or problem by the GM without the scene changing in time or place. Characters may also die in between these exchanges as well as certain characters simply vanishing or becoming suddenly scarce altering the scene, meaning scenes are less structured in RPGs than fiction. Thusly, within the context of RPG Narratology it is probably more befitting to call these units Episodes instead of scenes.

An episode in the context of TRPG narratology is a related grouping of Play Units where the setting/background does not have to be fixed. An example of this is a conversation between two PCs while walking through a magic portal beginning before they walked through and continuing through and on the other side, the backdrop changes radically but the episode is composed of the exchanges between the PCs.

This somewhat transient notion in TRPGs can be difficult when trying to translate between traditional narrative and TRPG narrative especially in such instances as trying to blog a personal (or a character’s) tabletop experiences. Those that blog their experiences around the table may try to demarcate portions of the campaign by Session instead of by traditional narrative units or even those of TRPGs being discussed here. A Session being a limited time spent actually playing the game with others and often a series of Sessions will compose an adventure and/or campaign.

When writing or setting up for episodes a GM need only rely on the key exchanges that end on or lead to a desirable result for them. Basically, the GM will want the PCs to end up after this series of exchanges in a place or situation that either leads directly to another planned episode or that which they believe that they can work with, giving them fodder for more episodes further down the line.

Keeping Play Units and Episodes in mind a GM can structure their thoughts and ideas while running the game and writing for their campaign. A game-master can learn to keep tidbits of info in mind and group them together later when it comes time to act on them in-game helping to form the plot threads that run through campaigns which the GM’s writing and narration helps to bind together into adventures.

Multiple related Episodes will accumulate to build an Adventure, which may or may not be consecutive or broken up amongst episodes that take the Campaign in different directions or digressions that will matter later connecting to other non-contiguous episodes or future episodes. In fiction, this is Plot/plot lines. Plot (McKee, pg.43) is a sequence of events divided into Scenes with each single scene often presenting a single event all driving to a conclusion. For the purposes of this essay there is no distinction between Plots and Subplots.

A minimum of three scenes construct the traditional plot in fiction with a beginning, middle, and end type of striation within the text. Likewise, in a TRPG, plot consists of three vital exchanges or episodes, which are Presentation, Complication, and Twist. The building blocks of a TRPG plot are a series of Episodes, which are bundles of Play Units guided by the GM and a ruleset with a path blazed by the Players. TRPG plots are the result of the informational interaction of these three entities.

In addition, as episodic structure is spread across real-life and the imaginary stage of the game world, Plots in this context are very mercurial and apt to change direction and nature suddenly and unpredictably. For this reason, it is most useful to refer to TRPG Plot as an Adventure. An Adventure is a single plotline that can be followed through a campaign referring only to the game and meta-game elements necessary to communicate said plot.

Scenario

Another very similar but slightly different informational structure to Episodes within RPGs are Scenarios. A Scenario is virtually identical to an Episode but has a definite self-contained beginning, middle, and ending structure. An example being a short combat or random monster encounter, this does not mean the enemy is dead at the end but the battle definitively ends. Other scenarios or episodes can lead into these and a scenario can either terminate a story thread or lead to the next episode/scenario. In other words, a Scenario is a self-contained Episode but is not equivalent to a One-Shot Adventure.

Adventure

An Adventure is an extended section of a campaign, which has a beginning, middle, and an ending. Adventure would relate to a story arc or group of chapters in fiction writing. Standalone adventures or One-Shots would be similar to a short story in this context. An adventure module is essentially gamified fiction and so a completed adventure always has a recognizable beginning and a definitive ending. This ending may or may not lead into another adventure however.

The beginning and ending are somewhat inflexible giving the GM a definite starting point and a definite ending point but the body of the adventure is and should be very flexible. The middle may be adjusted as the PCs play through it allowing them freedom of movement and exploration while the GM invisibly guides them to the end. This structure of linked episodes and/or scenarios allows the GM to improvise more effectively in response to the indigence of the PCs and in response to the creativity of Player decisions.

The Beginning of an adventure starts with a vital episode called a Presentation. Presentation refers to an exchange initiated by the GM that presents something to be solved or acted upon by the Players in such a way as to lead them into another scene or episode. Although whether or not the players follow this to the next episodic component of the current adventure is unpredictable and may require the GM to put a hold on the current adventure to go on a player-fueled tangent. The beginning of an adventure can be composed of a single episode or scenario whereas the body can conceivably be made of a single episode it is more likely (and fun) to be a chain of episodes leading to a climax or certain ending conditions.

The middle or main body of the adventure will be a series of linked scenarios and/or episodes. These Episodes and/or Scenarios involving locations and incidents which are all connected in some way, preferably each leading into another rather than just a series of events happening one after the other. It is in this part of the adventure a vital episode called the Complication should occur. This plot component throws in an unexpected obstacle at the Players which they must overcome to proceed to the end.

The ending is a definitive endpoint where there is a requirement that when fulfilled the PCs have completed the adventure bringing it to its end. Of course, just as in fiction the GM may continue as an epilogue to the adventure in order to finish off any stray plot lines or character subplots otherwise eliminating loose ends that do not lead to another adventure. The end is also where an episode called the Twist can occur. This is an unexpected turn in events that complicates the situation for the Players and serves as the final obstacle or a final surprise. Adventures propel the characters and thus their players through this shared world, which they not only can alter through the actions of their characters but also help to construct episodically. These shared adventures can themselves link together into a campaign.

Campaign

The Campaign is the largest component of a tabletop RPG composed of a series of related Adventures. An RPG campaign is analogous to the novel in fiction with story at the heart of both forms.

This brings us to the overarching super-structure underlying both fiction and TRPGs. In fiction, this structure, composed from the bottom up of Story-Beats, Scenes, and Plot, is Story. A Story is the text resulting from the totality of the aforementioned structures with the addition of characters, details, and the background (that may or may not involve world building) in which the events of the story take place. The fictive element most analogous to a Campaign is Story.

Briefly, story in terms of this essay is a piece of fiction structured to elicit a certain reaction or reactions in the reader. Stories are structured by careful choice of material and the arrangement of constituent parts into a narrative. [Beacon Lights of Literature 1, pg.5 – Poe’s Theory of Short Story] The most basic elements of story that also correspond to RPGs are character, plot, and setting. Of course, these underlying structures that authors of fiction use to construct their stories vary so much from those of TRPGs at this point it is probably more efficient to call Story in terms of tabletop RPGs a Campaign.

A Campaign is the totality of all of the game and meta-game exchanges, participant characters (both PCs and NPCs), any material that the GM used regardless of original source or authorship, and the diegetic game world where the campaign has taken place. It is from this accumulation of detail and narration from which the participants can extract their personal narratives from the point of view as either their character(s), as a player, or a combination of the two. It is also in this higher tier structure where the world-building occurs as world-building is done through the accumulation of information gleaned from the gaming material and from the information drawn or resulting from certain exchanges and demonstrated in certain episodes. These details are often noted down by the GM so that the PCs may revel in or return to these certain facts about their imagined communal world.

A Campaign is a long-term ongoing RPG game that has at least one arc that takes it from the beginning to the end. Note that a campaign will often have several arcs and plot threads. Each game session builds on the next not just in terms of character experience but also in the accumulation and generation of story threads where at least some of which helps to lead to the conclusion of the campaign.

This long-form allows the GM to gradually build the in-game world as well as allowing the players to evolve their characters and make a mark on the game world possibly even influencing its course as well as the course of the campaign itself. Thus the game world is always seemingly in flux built around and accumulating certain facts about itself which serve to anchor believably (and replayability) in the diegetic frame. In RPG terms, Story is not the product of any single author but a group with a certain share of that group with their hands and feet within the fictional world of that story.

The Structure of an RPG in Ascending Order is:

Play Unit – A bidirectional exchange of information between participants analogous to the Story-Beats in fiction.

Episode/Scenario – A collection of play-units that paints a situation that leads somewhere analogous to a fictive Scene.

Adventure – A linked collection of episodes and/or scenarios with a definitive beginning, middle, ending structure analogous to Plot or a Short Story or Book Chapter.

Campaign – A collection of shared adventures analogous to a fictive Story or Novel.

World-building occurs in tabletop RPGs by the sedimentation of details and information born of the bidirectional flow of Play Units structured and augmented by the rule set. That building the more complex structures that constitute roleplaying games and their worlds as the game is played. This organized flow underlies everything about tabletop role-playing games.

Summation

This theory of the organized flow of information is meant to be not only a ludology device but also a practical tool for those involved in the writing, creation, and playing of roleplaying games. In my experience and in my research including the reading of various other RPG theories this one rings the most personally true and has been of practical use in my own writing for RPGs.

Related Blogs and Articles

All of these cited works are authored by me unless otherwise noted. Each holds bits and pieces of the Organized Flow Theory as well as some narrow applications. The last is a purely mechanical dissection but I think illustrates a general knowledge on how the mechanics side operates.

Handling Game Flow in RPGs (Hubpages)

Building Tabletop Myths (Hubpages)

Tabletop Meditations #7: RPG Narrative

Tabletop Meditations #9: Campaign Structure

The Finer Points of the Frankengame

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

battlefield, the personal devastation realized when surveying the field of victory, roleplaying War. War can enhance a roleplaying game not just because of its opportunities for fantasy violence and power fantasies but because of its depth of emotion and intellectual involvement as well as the physical trials that characters must suffer. However, in the theater of the mind that is a roleplaying game, war becomes a mental landscape and its phases and components feature in that plane.

battlefield, the personal devastation realized when surveying the field of victory, roleplaying War. War can enhance a roleplaying game not just because of its opportunities for fantasy violence and power fantasies but because of its depth of emotion and intellectual involvement as well as the physical trials that characters must suffer. However, in the theater of the mind that is a roleplaying game, war becomes a mental landscape and its phases and components feature in that plane.

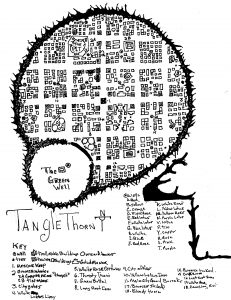

canny-jack (played by Isis) had been escorted by a contingent of city guard to an office near the White Rose Perfumery. The office was small, crowded with stacks of yellowed parchment sheets. Also scattered everywhere were small wooden ink stamps bearing various official seals from past regimes.

canny-jack (played by Isis) had been escorted by a contingent of city guard to an office near the White Rose Perfumery. The office was small, crowded with stacks of yellowed parchment sheets. Also scattered everywhere were small wooden ink stamps bearing various official seals from past regimes.

has any words with them, and they loot every corpse. In fact, loot is just one excuse they use to participate in the slaughter of unfortunate NPCs. What you have on your hands is every GM’s nightmare, a gaggle of Murder Hoboes.

has any words with them, and they loot every corpse. In fact, loot is just one excuse they use to participate in the slaughter of unfortunate NPCs. What you have on your hands is every GM’s nightmare, a gaggle of Murder Hoboes. adventure the expedition begins to fall sick with fever. At first, just a few torchbearers were sick and then a few porters. Eventually almost the entire adventuring party is sick even a few PCs are ill. The danger made apparent before the expedition. However, they assumed it couldn’t be that bad. After all, they had healing magic at their disposal. Now stranded at the center of a monster-infested morass they are bogged down with a sick and dying expedition. In addition, the longer they stay, the more likely more will fall ill. An invisible tiny enemy has brought them to their knees.

adventure the expedition begins to fall sick with fever. At first, just a few torchbearers were sick and then a few porters. Eventually almost the entire adventuring party is sick even a few PCs are ill. The danger made apparent before the expedition. However, they assumed it couldn’t be that bad. After all, they had healing magic at their disposal. Now stranded at the center of a monster-infested morass they are bogged down with a sick and dying expedition. In addition, the longer they stay, the more likely more will fall ill. An invisible tiny enemy has brought them to their knees.