I’ve recently published a new article on Hubpages/HobbyLark titled, “Building Your RPG Character’s Background Story”.

You can read it here:

https://hobbylark.com/tabletop-gaming/building-your-rpg-characters-background-story

Publishers of the Dice & Glory Tabletop RPG

Articles elsewhere concerning role-playing games in general and authored by our staff.

I’ve recently published a new article on Hubpages/HobbyLark titled, “Building Your RPG Character’s Background Story”.

You can read it here:

https://hobbylark.com/tabletop-gaming/building-your-rpg-characters-background-story

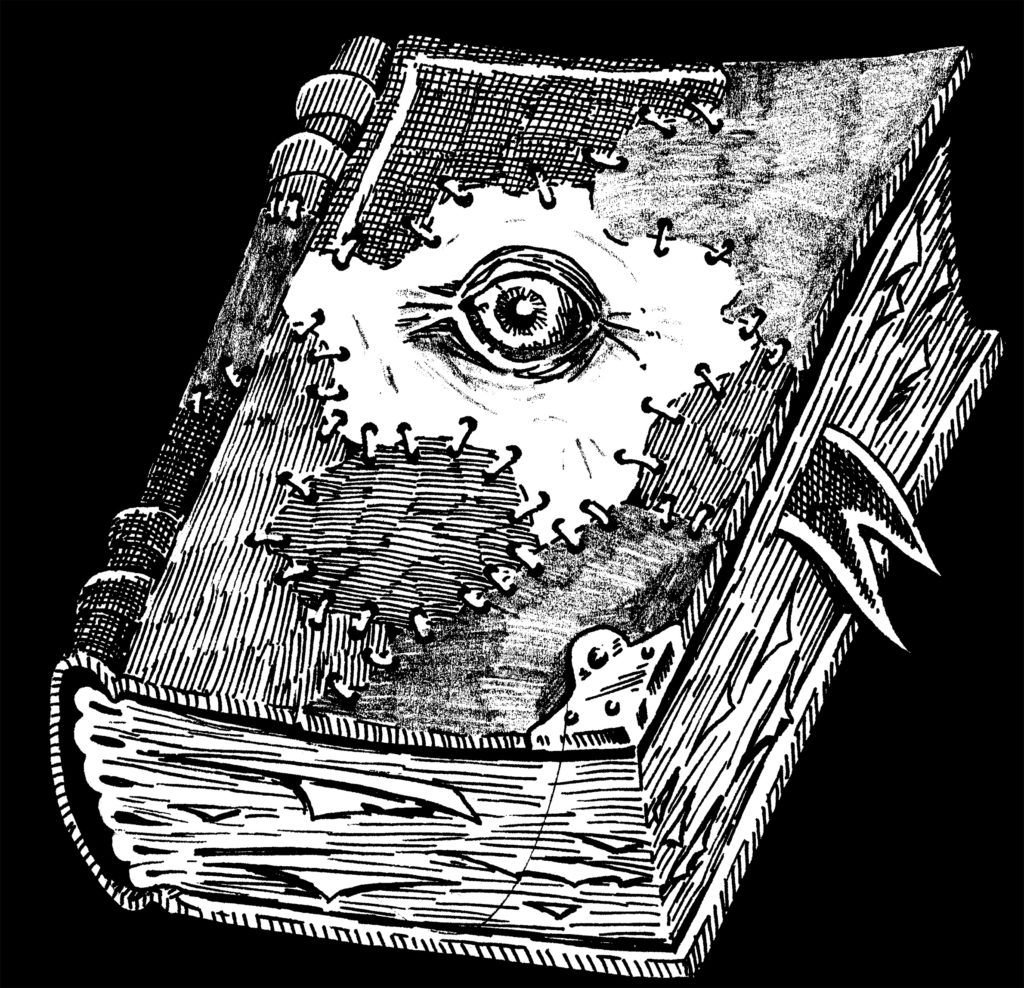

Characters begin to loot the dusty old room after slaying their foe, some monstrous undead thing. They find the typical loot, some coins, a few gems, and a couple of items. Their first impulse is to appraise the monetary value of the loot and calculate what the split will be. Then they find an old sword hanging on the cobweb-tangled rear wall of the room. When they reach it the Gamesmaster does something that they only half expected. The GM gives the item details that distinguish it from the rest of the loot piquing their collective curiosity.

Giving items a level of detail and a backstory much like a non-player character (NPC) increases that item’s role. The storied item will have a higher position as opposed to other items in the gaming narrative. This technique takes items beyond the role of simple spoils of adventure or a material reward. Note that gaming narrative is different from narratives in the traditional sense. The ‘beats’ of the game tend to follow a perpetual Sine-wave type pattern. High points on the wave being action/drama then dropping back to normalcy. Alternately, they can sink to a low point before the next rise.

Adding details and a history to any item meant for a PC to acquire helps keep certain players on track. This is especially true if the GM hints at the right clues and incidents relating to the item regularly. This can add flavor and detail to the game setting and add some complication to fairly straight forward campaigns. These specially designed items are not just treasure they double as tiny bits of the game world custom packaged for the players to explore.

To be clear, these are not exclusively MacGuffins. These specially designed items better serve to enrich a campaign. Storied items are not meant to serve as the central focus of a campaign. Nor are they to provide motivation for the group to go on a specific quest. However, they are meant to run the length of the campaign alongside their owners hopefully adding a richness of detail. In a way, storied items ornament a long-term campaign and provide the GM with adventure fodder.

Specially detailed items with a backstory can lead to more adventure hooks. These hooks occurring at the low points of the curve leading to the highs. These items possibly leading to an adventure within an adventure. Similarly, they can lead to side-quests galore branching off or intertwining with the primary campaign focus. It is another thread to weave into the fabric of the game-world. For instance, take a quite common but also much-desired item found in any fantasy campaign, a sword.

Any sword, after a morbid fashion, can give (or rather carve) somebody a red smile. However, the true value of unique items with compelling histories and as-of-yet unfulfilled destiny is to Gamesmasters. It is a boon. GMs should try to write up specially designed items. These the players can discover, quest for, win, or loot in the normal course of a campaign. It does not have to be magical or have special powers. However, if that is the carrot onto which your players will bite then by all means.

However, the item needs to be immediately visually (meaning descriptively) interesting. At least to one of the players. This serving as the initial hook. It also does not hurt to try and tailor the item to specific characters. However, always remember to try to attract the players’ attention to it. For an example, let us use a Chinese Dao. It has a long tassel at the pommel and broad, heavy machete-like blade.

There is a sword hanging on the far wall all covered in the same dusty sheet of cobwebs. It appears to be a Dao of a particularly high quality. You can make out the glint of gold, silver, and the glitter of gems. As you look closer, there is a strange faint flickering as of flame. Even from underneath the webs and centuries of sedimentary filth you can see its strange light.

There are a few methods to snag the players using these characterized items. They are very much like those used in writing adventure hooks. You must ask yourself two questions. What type of weapon/item is it and what have the characters been looking for? Additionally, is it something they can pick up and use? However, can the characters also explore its uses (immediate bait). A brief example being a weapon with special features. However, those abilities only make it a more formidable weapon when one learns how to use those features. Of course, this last aspect would rest almost entirely on the system within which you are working.

This brings us to the “Bling.” Bling being the visual details that mark the item as one-of-a-kind. The flashy part of the description. The sole purpose of bling is in attracting the attention of the player(s). Basically, the visual details that tempt them. Start with the main details such as what material(s) make it up. Is this material out-of-the-ordinary or exotic in some way? Are there gems and what kinds, and how are they cut? Are there engravings or inlays? Is the engraving a message of some sort? Can the players read it, or do they need an interpreter? What language is it in? Is it magical script or Elvish? What is the handle wrapping made of? Do the materials, design, or make give hints as to its regional/historical origin?

The Dao blade is of silver and the guard and pommel gold with the engraving of patterns resembling flames. There are characters along the blade inlaid with platinum. They appear to be in an archaic northern dialect. Alternating jade gems, rubies, and deep blue sapphires all cut en cabochon along the guard’s edge sparkle. The tassel that extends from the golden pommel is fire silk and there is a large dark red carbuncle at the base of the blade. This glows with its own flickering flame light. The grip is wrapped in the smooth skin of a metallic blue sea serpent.

Details construct this special item within the minds of your players. As with the initial appearance of an NPC, the initial description of the item’s general shape and condition affects its perception. Its appearance provides fuel for any perceived or applied “personality”. When in doubt use an engraving bearing a name or saying for an easy addition and telling detail.

The details you use can be battle scars, personal/familial heraldry, makers’ marks, or decorations. These can have attached stories and may play to a certain theme. Visible imperfections will mark the item as unique and may contribute to the backstory. These can be from the original artisan’s hand or even a defect in the base material itself.

The important thing to remember is that these details should mark it out from the rest of the swag. It should be unique compared to that the characters may have come upon up to this point of the game. It should remain at least somewhat unique throughout the campaign. After adding details with at least one marking it unique, a brief history or backstory is necessary to finish it. Certain details should be invented exclusively for the item based on its history.

The blade of the sword shows a deep nick. Apparently, an old battle-wound from an especially powerful blow. Additionally, there is a patch of very pale scales among soft deep-blue scales on the grip. The angler you have asked about the skin on the handle mentions off-handedly an old fisherman’s yarn. It is about a vicious sea-serpent nicknamed ‘Old Scar’ due to the patches here and there on its hide earned from the harpoons of defending sailors.

When writing the backstory keep in mind the group resources. You should know what abilities or resources the group possesses to let them probe the backstory of the item. Psychics and spell-casters with certain augury or ESP-effect spells/powers can help by catching tempting glimpses. They can even catch bits of dialogue and other certain clues. Like about who made it, owned it, where it has been, and its unique history. Alternately, if you are trying to hold back certain details these types of abilities may ruin the clue chasing. They may even spill the whole story out all at once. This is when it pays to be subtle. Hone the GM fudging skills using the rules governing these powers to your advantage.

Investigative abilities are certainly suited to engage this type of GM-device. Using science and/or lab skills to gather information in a CSI-like mode is yet another dimension to keep abreast of. In fantasy settings such skills as alchemy would qualify for this mode. However, this is especially so in a modern setting. Do not discount library research either. This allows the GM to create accessories to the item like works that collect lore or document legends. Even antiquarian guides not to mention antiquarian-type characters become more important. These character archetypes are probably the most equipped (besides certain psychics) to delve into such campaign aspects. These types of characters and skills are already, or should be anyway, motivated to participate. They will make it easier for the players to dig into the backstory.

The backstory will consist of a few basic points. Where was it made, who made it, and who was the last owner? Alternately to the latter, who was the most significant character in the item’s history? Pick out the individuals in the backstory that matter the most in-game terms. This can be the craftsman, the original owner, the last owner, or the one who stole it. Only one to two points are necessary to create a rough character outline. Other details can be filled in on the fly. NPCs in the backstory do not require full game stats but need only to communicate impressions to the players. Note that the main characters from the backstory will have names and those names may be recognizable as connected to other legends and stories etc.

When conceiving these special items, the GM must ask themselves a few questions to get the creative juices flowing. How recognizable is the item itself? Does it have a reputation? Did the maker/owner of the item have a reputation? Or is there a folktale or story circulating around them and thus the item? Does the item have a name itself? Players and their characters may be asking these questions themselves. Therefore, the GM should have answers ready typically through the mouth of NPCs.

The blade could have been forged somewhere to the south. Where the high-grade silver used for the blade is refined from lead. This is also where the skills necessary to craft such a blade are not rare. There is a village in a remote area of that region rumored to raise the dragon-worms that produce the extremely rare fire-silk, but no one has seen newly spun fire-silk in an age.

The next step is making the “bling” jive with the history you have written. Turn the details into clues. First, make sure the attached background NPCs, important details, base materials, and general craftwork go together. Make sure that they collectively put the story of the item forward. This does not mean, however, that all the details need to match or correspond in some way. You can also use bling to put forward a telling contradiction between details. Alternately, you can use details as a device putting to the players a puzzle, a paradox to be deciphered. Using the details in this manner can serve to perk up the players’ curiosity. Or help to coax them along the path the item reveals to them.

The characters on the blade say, “Death to the Usurper of the South!” The sea-serpent skin is from an extinct variety of sea serpent. It was known as the Sapphire of the North Seas fished by enterprising fishermen. Additionally, there are characters engraved around the edge of the pommel that are hard to read and badly worn. They mention a name — Master Snake Commander of the… — but the last few characters have worn away.

The backstory the GM creates can lead to a side quest (i.e., away from the main thrust of the campaign). It can run a parallel course, intertwine with the main story usually joining at a certain point. Or can be any combination of the three. Intertwining the backstory of the item with the current campaign direction can keep a wayward player engaged. Doing this by merging their character’s story with it and thus the campaign dragging them along by their curiosity. It can also help to engage players in a concurrent story if the current main plot is not keeping them hooked. At a certain point it can serve to lead them back to the main story at a certain point.

Intersecting points in the main thread with the story of the item can be multiple. Giving a little tidbit of information to the players each time they reach such a story point. Such as while traveling south from a northern frontier the PCs get the related odd tale or a small bit of conversation. Each of these shedding light on specific aspects of the item(s). As the PCs chase down their main goal they will run into the points of the game where the special item figures in.

On your stop-over in the village, the town-drunk regales you with an old story. Its widely known in this region. It is about the young son of a wealthy merchant. The merchant’s riches were said to be held in uncounted smooth-cut gems. Some of which glowed with an inner fire of their very own. A barbaric warlord descended from the mountains with his horsemen and conquered the whole of this region. The merchant’s family slaughtered; their riches pilfered. The son ran to the provinces of the north vowing vengeance upon his return…

The backstory of the item can expand upon or add to the campaign world. Just as would a well-constructed NPC but unlike an NPC its details are passive. It requires the players and their characters to investigate them actively. Or have an NPC recognize and communicate what they know about it to the player characters (PCs). Its added flavor if nothing else but it requires the participants to actively engage it. To taste it as it were. This is of course barring any supernatural abilities that may grant the item agency.

These types of specially designed items will add to the game-text for the group. Especially so for the specific player whose character owns it. However, the latter choice may alienate others in the group. Unless you are trying to pit them against each it is probably not the best idea. In this case, tailoring the item to a single character is best. Add in storied items for the rest of the group gradually not all at once.

In fact, it might be useful for the first item to lead to the next and that to another. This lets the GM bait the entire group with each item. Each providing a single piece to a puzzle that begs players to solve it. Or a story that they cannot help but want the conclusion to. Not to mention the items should be useful for the characters in-game. This is outside of the clues and backstory. It is particularly important to never forget this. If it is useless in-game, why would they keep it? Always play to the players’ practical side. However, at the same time use their greed to hook them and their curiosity to propel them.

Players and thus their characters tend to become attached to specially detailed items. Much the same as favorite NPC’s if the backstory and details are just right. The players may even face a hard decision later on in keeping a beloved but mundane item over an upgrade. A rare case of emotional value triumphing over practicality. A well-crafted item can contribute to the overall quality of the game that is if your players are willing to bite.

Designing a non-MacGuffin item as you would a full-blown NPC has its rewards during gameplay. The item can become a worldbuilding aid as well as evolving into a story point in and of itself. It deepens the game world and can help to engage curious even greedy PCs rewarding them not just materially but with emotional payoff as well.

Games-Masters (GM’s) are already like mad scientists modifying their current gaming system often on the fly. This is through either in-play rulings (e.g. building precedence) or directly fabricating rules or guidelines. This is sometimes to patch deficiencies or fill in gaps discovered during play regardless of the potential for unforeseen consequences. Often, GM’s tinker with their current system adding in rules or new additions. However, they are often hesitant to rebuild or mess with the engine of the system.

However, GM’s can achieve some amazing results by doing just such a thing. GM’s can completely rebuild the machinery of a game with only some basic knowledge. Games-Masters can go further than simple modifications stepping into the shoes of a game designer. That is without stepping blindly onto the unsteady ground of game creation from scratch but still achieving something very similar.

Modifying existing systems is the gateway to creating one’s own full-on tabletop rules-system. However, like Frankenstein’s monster, missteps and using the wrong parts can lead to disaster. All GM’s who have ever run a few games know of the vicious cycle of modifying the modifications. All in service of keeping a campaign limping along.

The Frankengame exists in the realm between the patchwork game and game-creation as a sort of gateway. Here, like Doctor Frankenstein in the graveyard, a Games-Master can get closer to being the creator of their own system. They are starting not from scratch but from the constituent parts dug-up and snatched from sundry and various places. They will know the resulting system more intimately allowing them to avoid the vicious cycle mentioned above. In addition, this process sharpens the mechanical skill of GM’s allowing them to be better able to patch any flaws on the fly.

A Frankengame, like its namesake, is created by taking the operative portions of a game-system referred to here as Modules. Then taking these from multiple other games and slamming them together creating a functional homebrew mash-up. This, in an effort to maximize your enjoyment around the table. This is regardless of whether you or your group are more interested in a more Simulationist or Storytelling gaming mode. Alternately, also useful if you and they enjoy a simplified set of rules or rules-heavy systems.

The newly assembled game should function reasonably well enough to be used as its own standalone tabletop RPG system. Metaphorically similar to the human corpses that contributed to Frankenstein’s monster, you stitch a Frankengame together from the working organs of other games. This is given that all tabletop RPG systems have functional organs that allow them to tick. They share a common anatomy.

A roleplaying game system as a unit is a collection of interacting rules that help to determine the in-game actions of characters. This at least according to Wikipedia. It is also a system of interacting modules, a package of rules and details, each module-package being a subsystem. Modules allow for the construction of in-game items and resolution subsystems. Sometimes they even add to a core resolution system modifying it to some extent based on circumstance.

The common Base Modules of any RPG System are the Combat System, Skill System, the Mystical Engine, and the Object Subsystems. The Mystical Engine being the governing mechanic of the magic & psionic systems as well as any similar such ideas. Object subsystems being the component governing such in-game objects as weapons and armor. The Character Creation system/mechanic can also be included in these modules. This is especially so if there are several different methods presented for players to create characters in the materials.

Base modules are subsystems that handle a specific portion of the game but still have a wide enough reach as to be able to have further subsystems within them depending on their complexity. Note that the more complex the longer it takes to make a rule-call or task-determination. As stated before, these Base Modules handle a limited but still broad aspect of the game. This includes such things as Combat. For example, subdividing combat into such aspects as Vehicular, Barehanded, or even Armed combat although generally it still encompasses these. Similarly, expanding combat with smaller sets of rules or increasing complexity by adding a subsystem to handle one of the different and more specific aspects/scales of combat. At the center of all of these modules and subsystems lay the heart of the RPG, the Core Mechanic.

At the heart of the game system from which these modules branch is the Core Mechanic. The Core Mechanic is the principle that all the rest of the system works on. A Core Mechanic is in the simplest terms a formula for conflict resolution. Conflict in this context being an in-game occurrence where an impartial decision is required. Core Mechanics usually rely on a single die roll with certain modifiers added and may even rely on looking up that result on a table or even the number of dice rolled as in a Dice Pool. Most systems wear this on their sleeves so it is easy to get right in there and cut it out so it can share its beat with your homebrewed monstrosity.

A Games-Master/potential Doctor Frankenstein can simply add in or swap certain Base Modules or subsystems with those from another. Although as compared with assembling a completely new system, this counts more as transplantation. However, even mad doctors need some practice. True Frankengames are an actual fusion of at least two other games (hopefully more) and recognizable as apart/different from either of them.

Most groups already modify and patch together isolated bits to their favorite systems. Especially when incorporating tweaks, hacks, and divers guidelines/tools from the internet. Taking that farther into Frankengame territory can enrich the Games-Master’s knowledge of tabletop roleplaying systems. But it also builds a custom engine that fits perfectly with their style of play. In addition, the custom engine can answer the needs and wants of the GM and their group. The reasons to begin such an endeavor are manifold.

This last point can be satisfied, and usually is, by simply expanding the rules or transplanting specific chunks or modules. You can use your own invented rules or those borrowed to patch an existing system. However, this births something more of a hybrid system rather than a genuine Frankengame. A true Frankengame pushes even further across that line.

A Frankengame maximizes your vision for your game world, allowing a deeper level of believability (suspension of disbelief). Therefore allowing for deeper emotional ties and freeing you and the players to role-play more within comfortable and familiar bounds. These bounds better fitted to the tastes of the group. However, be warned this is reliant as much on the conduct of players and the GM as a function of system mechanics.

To begin the process you have to start with the most vital point of any roleplaying game system from which all else circulates – its core mechanic. From here, you can move on to the other points of concern. All other aspects of the game from character creation to all of the modules and subsystems rely on it. They may modify or use it in slightly different ways but all require it to function. There can conceivably be more than a single Core Mechanic. However, rules conflicts and exponentially expanding complexity result from this. Therefore, unless absolutely necessary to your vision it is ill-advised to add more than one.

This does not mean you may use more than 1 type of die in the core mechanic, just that the core mechanic remains the same. An example would be the D20 mechanic of a modified dice roll to meet a set target number. Conceivably, depending on a given subsystem you can use different types of dice or a variant on this basic concept.

Next, try to decide which subsystems or modules will be necessary for your game to both function and include those aspects, which you desire. Note that a module can include more than a single subsystem as well as ‘patch rules’ to shore it up. You also have to figure out what modifications are necessary to fit these subsystems to the Core Mechanic. There are 4 or 5 subsystems and modules needed for most RPGs. These are Character Attributes, Skill System, Item Generation, and Combat System, with the Mystic Engine coming in as optional. Most other tertiary systems are a combination of the aforementioned mechanics such as Character Generation and Monster/Creature Generation. These using rules and systematic processes connected to the subsystems to produce an in-game character. Their abilities embedded in or functioning within the applicable game modules.

A word of advice in these first few steps, keep in mind how disruptive players might take advantage of the system and its components to break the game. Running some of the still-bleeding rules past a rules-lawyer, min-maxer, or power-gamer can help to mitigate their impact on a fresh Frankengame. Also, stay aware of any gaping holes or gray areas in the rule-set as well. Although you may want to build in some gray areas. This allowing GM rulings to take precedence in certain areas, but gaps should be documented.

Once you have all of the guts for your monster you should begin to organize them. Take note of what parts need to be rewritten or modified to work with the Core Mechanic. Do not forget the other smaller parts as well. You also need to think about how these may interact. Compile a list of each mechanic with notes on how to deal with any inherent flaws. Keep in mind any original bits that you have that will help stitch it together. Drawing a crude diagram of inter-system connections will also help. While dissecting the desired parts from your material RPG-systems, you should throw out any patch-rules that act as connective tissue to other subsystems that you are not taking. However, make sure to keep any for those that you are.

After you have all of the raw material on the table and have a good idea via a list, possibly a diagram of how to put it together, all it takes is stitching it up. After that, make a few test rolls and quick scenario runs to make sure that at least initially it’ll work. Patch-rules serve as your sutures to sew these bits and pieces together.

Rule Patching is a fundamental aspect to creating the Frankengame. It is adding in clauses often based on certain situations to plug up a “hole” in the rules. Alternatively, they can also clear up any unintended gray areas as well. These patches serve not just to correct flaws but are also the connective material between subsystems so that they can function in unison.

Essentially the process for writing a Frankengame is as follows:

Creating a Frankengame helps to create a custom system for your group. This has several potential benefits. However, it does take some trial and error even after doing the work of piecing it together. Sometimes it will rise up and be super other times it’ll just strangle you. The main benefit of participating in this activity is learning about the construction of a roleplaying game system on a blood & guts level. In any event, it can give you a firm grounding in the basics of RPG construction.

In addition, exploring a new system with parts that are already familiar can be fun inside of itself. This is especially so when probing for flaws, gray areas, and holes. Even on a dry run of the Franken-system, the group should not be completely lost. The familiar parts may initially give players a steady base from which to explore experiencing genuine surprise when they stumble into new unfamiliar territory. Being the mad scientist type and patching together a Frankengame not to mention hacking established systems apart sharpens your understanding of how RPG systems work. Maybe grafting together a FrankenGame will put you on the road to writing your own original game later on.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

Non-player characters (NPCs) populate Gamesmasters’ game worlds providing a life source alongside the vitality injected by the player characters (PCs). Unlike PCs, however NPCs do not need to be complete characters. The level of completeness of an NPC is directly related to their level of intended interaction with the players. And to a lesser extent their role in the campaign or in a given scenario.

Those constructed to have some individuality identifiable by the players and even a modicum of believability can make the difference between a bland, artificial environment and a vibrant, exciting, living world. Applying layers of detail is a proven technique in NPC design that can payoff in spades during play.

A believable NPC can be described as an interesting, engaging, and memorable character. This is in addition to the fact that they are likely to exist in the campaign world in the first place. To create a believable NPC the GM can employ five layers in their construction. These five layers are:

The first concern when constructing an NPC is the level of detail needed. This is preliminary and aside from a quick rundown of each of the five layers. Simply inserting a single generic item in each layer can quickly generate mooks (nameless fodder) or a background NPC. However, these will be suited only to limited contact with the PCs. The level of contact an NPC has with the PCs is important. This as you do not want to waste time adding minute detail to a character that shows up once, says next to nothing then has no other significant/repeating contact.

Game masters should have a basic hierarchy for their NPCs besides the main antagonist(s). These would be (in ascending order): background, foreground or limited interactors with limited appearances, those with limited interaction but the potential for multiple appearances, frequent interactors even if their appearances are limited, and those who interact regularly with the PCs.

The higher up you move along the NPC interactor hierarchy the more detail needed. NPCs can move up the hierarchy or become elevated by ongoing interactions even if not designed for long-term existence. These gaining added detail either acquired from play (shear improvisation) or details and minutiae added by the GM. Often this occurs as a response to player inquiries or in an effort to give the NPC extra story weight. After determining the interaction level of an NPC, the very next concern is Archetype.

Archetypes, stereotypes, and tropes are useful tools in the hands of a talented GM. The latter pair are often considered cheap tricks (especially stereotypes). Stereotypes can if the GM is not careful or sufficiently creative, become cliché. And if the GM is not mindful, offensive. Archetypes carry the connotations of role, skillset, and ability. Stereotypes convey assumptions and preconceptions about behavior, motivating factors, and “genetic traits.”

Common stereotypes found in fantasy tabletop roleplaying include Evil-Murderous-Orcs, Suicide-Attack-Goblins, Bad-Guy-in-Black-Adorned-in-Batwings-and-Skulls, the Common-Thug, etc. These are trenchant and brief descriptions with an attached assumption.

An archetype on the other hand is a sort of blueprint. It is often built into or associated with various settings and works of fiction. It gathers together certain attributes. These presenting a general sketch of a character and possible patterns of behavior packaged together with general appearance. The archetype should be selected with the NPC’s role in mind. Stereotyping, on the other hand, is shallow shorthand communicating specific character traits to players. based on a large social/economic/regional/ethnic group. An especially useful tool when there is limited playtime, while in a pinch, or in a faster-paced part of the game.

Certain classic archetypes found in roleplaying include the Do-Gooder-Paladin, Prefers-the-Wilderness-Ranger, the Might-Makes-Right-Barbarian, and the Sticky-Handed-Backstabbing-Rogue among others.

Tropes, another tool in the box, allow the use of a shorthand statement to easily communicate certain aspects of NPCs. These can be as short as a name for a fantasy race or profession. Perhaps a short description not containing a value judgment or opinion in and of itself but carried by familiarity. GMs can use tropes to influence the players’ in-game actions dependent on their reactions. If the group groans at the mention of specific tropes, the GM probably shouldn’t use it. Unless, of course, trying to raise the ire of their players. This actually holds true for stereotypes as well.

Examples of common fantasy tropes include the Knight and variations on, the Archer, the Spell-Slinger, Half-Dragons, the Scholar, etc.

The second NPC layer, distinguishing physical features and build, begins to grant the archetypal NPC more individuality. Race, in roleplaying terms, is a way of communicating the most general physical features and behavioral patterns to the players simply by attaching a label to the NPC. Race is a combination of stat templates and stereotypes promoting a general idea, right or wrong, about personality and role. Again, a simple mook character does not need much more than that. Maybe some equipment. But a well-rounded NPC would need a few more visual cues to deliver some additional information to the players. This information can include a verbal exchange. This is good to use with a simple encounter as well to drive home the NPC’s intentions.

An NPC’s face is a roadmap of experience particularly if they have had an especially brutal life. Acquiring scars, tattoos (which can carry their own symbolic meaning) or losing teeth, eyes, noses, etc. adds character. Prototypical pigmentation that carries meaning in the game that the players can clue into, is also useful. Even a deep suntan and very visible tan-lines can reveal occupation before the GM names it. Alternately, regional racial features can distinguish an NPC from the racial norm. For example, a lighter shade of green or very tall points on the ears. These hinting at a different origin than the racial norm can communicate some ethnopolitical information expanding the game world. Physical disability can also add layers to the character. This due to birth defects, the mutilation of war wounds, or more specific instances of physical trauma; abuse, ritual mutilation/scarification, accidents, or draconian punishment.

Costume and equipment, the next layer, can be used to express the character forthrightly. Alternately, it can hide their true nature or intentions, heighten the anxiety of players. Or it can feed them hints/clues as to the wider world, the NPC’s fighting ability, skillset. Or reveal otherwise unexpressed aspects of the NPC’s personality as well as connections to other individuals or organizations. Mooks and background NPCs need only the gear to carry out their brief and likely, temporary purpose with perhaps some token details.

NPCs should have an equipment list comparable to their interaction level. As well as a role and an appearance that distinguishes them more as individuals from the lesser interactors. The players should take one look and know that these are more than just nameless minions. Personal items should be on this list, which can give clues to their religious beliefs, sentimentalities, and pastimes. Their costume can also reveal that the face they are presenting to the players may be a façade. Details such as neatness, quality, and the relevance of clothing style or equipment used to hide their true nature.

Here, certain visual tools, particularly heraldry, are very useful. An NPC warrior with a family crest or striking heraldic image across their chest is set apart from the crowd.

Another very important point when building an NPC is what skills they have at their disposal; their skillset, not necessarily their whole skill-list just the ones they are likely to use in-game. This including their combat ability and fighting style. They should have the tools required to make use of these skills and implements cogent to their combat style. Variation in combat style can demonstrate personality during a fight even without any verbal communication.

NPCs can also have customized gear identifying the piece as their personal property. Also, keep in mind the symbolic significance that the weaponry you equip your NPCs with can convey. For example, a spiked club indicating a real brute and probably a powerhouse.

Ultimately, personality distinguishes vibrant and detailed NPCs from simple mooks. The previous four layers can help to steer you towards a disposition that fits with the rest of the characterization. Alternatively, you can start here then make the rest of the layers agree with (or disguise) the predetermined core personality. Personality feeds into attitudes, reactions, and displays of emotion based on the surrounding world and towards the PCs. Personality can be conveyed in brief exchanges before combat, inciting comments, or during any kind of verbal interaction.

Quips and a nasty comment in the right place in an exchange can convey a lot. When it comes to straight-up combat NPC disposition will be reflected on many levels. This includes levels of aggression and the strategies, techniques, and types of attacks employed. Personality influences weapons and equipment as well. A character that desires attention or is a showboat will desire a level of flash or bling others will not. This can also determine how they decorate their gear. Comparatively, shy characters that have no desire to be the center of attention will wear less ostentatious clothing/gear. Likewise, a shy character who deep down craves the attention that they cannot bear to pursue may wield something flamboyant in battle like a scythe. The personal taste and interests of high-interacting NPCs should not be discounted.

The GM can use an NPC’s personality to surprise the players. Subverting tropes using an unexpected personality or displaying contradictory behaviors to what is expected. This can also subvert the apparent stereotype of an NPC. It can also be contrary to what is expected for one of their archetype, especially through reaction. Just take the previous example of a shy character wielding a scythe. However, NPCs should react at least somewhat realistically to the actions or even attitudes put forth by the PCs. Take into account what the NPC’s goals are, what they can read about the PCs visually. Similarly, take into consideration any raw gut feelings, unanalyzed emotional reactions, and disposition that they may have. The NPC’s attitudes towards the PCs are of note. What the NPC has experienced outside of the players’ purview influences their opinion of the PCs.

Another tool that should be used sparingly if at all is personality quirks. Nevertheless, an obvious quirk or tick can overpower an NPCs other qualities. It may become their singular defining characteristic in the eyes of the players. For the most part quirks, not to be confused with habits, have the effect of creating a character that has been set up from the start to be a one-trick pony. Obviously, this is not the best idea for long-term NPCs. Although it can help to single out a character that may only appear once or in a limited capacity. In this case, it will be their only memorable characteristic.

However, this can lead to gimmick personalities, which are essentially a form of bad stereotyping. A ‘gimmick personality’ is where all of the character’s actions and reactions revolve around their quirks or a single unique personality trait diminishing them to an unchangeable monolith rendering them utterly predictable. Quirks should be used sparingly and be reserved for one-shots unless somehow the quirk is not so ostentatious. Subtlety is required for use with recurring NPCs.

Habits and vices, unlike quirks, alter character behavior adding to personality depth. A habit is a behavior that the character will participate in as a matter of usual business with some regularity. The most obsessive types of which you could set a clock to. Some habits are dictated by occupation e.g. a clerk opening a store at around the same time every morning. But the primary concern in regards to NPC’s are personal habits.

Personal habits are those that NPCs have acquired in order to make their lives easier, out of a sense of security, addiction, or tradition. Personal habits at times are dependent on the character’s vices as well. Vices are behaviors the character participates in willingly for personal pleasure. Keep in mind that an NPC will carry the artifacts of their habits and vices as personal items. These are keys, lucky charms, mementos, paraphernalia, etc.

Most NPCs do not call for naming unless of course, the PCs ask. And as unpredictable as players can be, you can never be quite sure when they’ll ask. Therefore, it is wise to have a list on hand so you can name NPCs on the fly. Be sure to cross off the used names so as not to have multiple instances of the same name in-game. To be fair it is probable to have NPCs of the same name. However, it is just confusing to the players during gameplay. Also, do not dismiss the use of nicknames or Homeric Epithets, which can be easier to remember in some cases.

Note that friends, family, associates, and contacts give nicknames. These are often terms of endearment that can be embarrassing to the so-named NPC and a potential source of humor. Nicknames reflect the character’s background to some degree. With nicknames, the NPC’s behavior and occupation/profession will definitely come into play in the naming. This does not discount a specific incident that may lie in the character’s past, however. Nobody lives in a vacuum and neither do NPCs. They will have relationships enmeshing them in a web that represents the social portion of the in-game world.

GMs have several options when it comes to the relationships of NPCs and the strength of those bonds. Family relationships include relatives, parents, siblings, spouses, lovers, children, friends, and partners. At the very least, they may have comrades that could miss them when they are gone. Relationships are dependent on a character’s background. But instead of writing out a complete background, the GM can simply make a list of connections between NPCs and organizations referring to it during gameplay as necessary.

All non-player characters serve a purpose in the game determined by the GM. They, as fictional characters, have no actual agency or motivation. However, to be believable they need to have an in-game reason to be doing what the GM has set them to. NPC motivation is often simple such as a service to appetite, revenge, greed etc.; for most NPC’s there is really no reason to go any further. Those that are higher in the interactor hierarchy however should have some goals set for them taking into account their personality and contacts.

These types of NPCs, those with goals, should display some agency. They take the steps to get the metaphorical ball rolling. This is done by starting rumors, setting out bait, paying off the right individuals. Possibly carrying out what they see as the proper action at the right time. The more goals an NPC has the more they should be fleshed out. This is because the more present they will be in the campaign.

The GM must decide, often fairly quickly, what an NPC is willing to SACRIFICE in the quest to achieve their goals and how strongly their motivation and personality fuel this desire to fulfill these goals. However, usually, only specific factors will push an NPC to the ultimate sacrifice. Such as those that are coerced with credible threats; their families will be killed if they do anything other than die in the attempt to succeed in their mission. This can elevate even the most generic mook beyond the Manichean model. This is especially so if the players discover this after killing them.

Archetype, physicalness, gear and clothing, skills of note & combat style, and general personality are required to build complex, lively NPCs. This five-layer strategy assists in generating, and fairly quickly, NPCs with enough detail to easily suit their roles and cover their intended interactions with the PCs while keeping the game interesting and varied as well as deepening the game world. However, true depth results from long-term development arising from interactions and reactions accumulating in player memory (and the GM’s notes).

All characters within a campaign, PCs included (hopefully), grow and deepen with time. The longer they are played the more detail they accrue eventually growing beyond their initial meta-purpose. Meta-purpose being the reason the GM put them into the game and for which they were initially written. NPCs that the players remember and include in their war-stories are the true measure of success. A completed and fully developed NPC should have several layers like a fresh onion. Should that bulb happen to get diced, a few tears, and not just the Gamesmaster’s, should flow.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

There was definitely a reaction on the part of the roleplaying community to my recent HubPages article “Why Do Orc Lives Matter?” This is a stream-of-thought meditation on that reaction as a whole and on the most common positive and negative comments. The original reason for writing the article in the first place was in response to a spate of Orc-Posting and the counter-reactions to the reactions. I also stated this in my introductory post for the article.

Note the article itself can be read here: “Why Do Orc Lives Matter?”

I appreciate the positive reactions, which were not as common as the negative but far more thought out and valuable. The most interesting reactions included mentions of maintaining Orc Armies and the Sentience of Undead creatures. The latter is actually a subject I have on the backburner but that is a stream-of-consciousness piece that philosophizes more about the nature and sentience of undead creatures and ghosts than adhering to any tabletop specifics or sourcing. These are the reasons I’ve never published it or worked further on it after putting a page of it down. I might dust it off in the future though. Note that not all of the positive comments agreed with the main thrust of my article but were civil and thought out plus the respondents seemed to have actually read the piece in the first place.

This document, an article from a miniature war game fanzine circa 1974 authored by Gary Gygax, was sent to me and I was aware of this document as I was conducting my research. However, it seems not to have a clear pedigree. At least at the time, I was doing my research so I could not really include it as a solid source. The main conclusion is that Gygax did not like Tolkien or his fiction. Although it doesn’t really matter how Gary Gygax felt about Tolkien when it comes to my article.

All that matters is that he was an influence on Dungeons & Dragons and the “proof is in the pudding” as it were. Tolkien is named in Appendix N as an influence and the Tolkien Estate did sue TSR over the use of Ents, Hobbits, and Balrogs to cite some obvious links. So, the influence of Tolkien on Dungeons & Dragons is very well-known and pretty much indisputable. Even in Gygax’s article, it says that both Chain Mail and Dungeons & Dragons were influenced by Professor Tolkien who originated modern Orcs, though his influence might be weaker on one than the other, it is still an influence and a solid connection.

Most of these types of responses were pretty much knee-jerk reactionary garbage most made before even reading the article itself or including a commitment to “never read it” thus making these posts utterly meaningless and ignored for the most part or responded to with “Read the Article” which elicited accusations of deflection. There were a couple of nasty responses, which I reported immediately. A few responses were puzzlingly long, that rambled about the article in such a way and I guess trying to summarize it and nitpicking details from varying game systems that just were so unorganized and confusing that I completely ignored them.

There was also a peculiar obsession on trying to shame me because of the title (all came off as a deliberate attempt to shame me into silence however). So let me be clear and reiterate – The article is asking a question that needs to be asked of our hobby because of the same forces that #BlackLivesMatter has risen to combat are tearing at our hobby, it is not gauche or insensitive and taste concerning this matter is irrelevant, the article and its title are relevant.

There were even those who claimed to have read the article and then still used the same dismissals argued against in the article proper.

Overall, the types of reactions throughout the social media platforms I participate in split right down the middle. This lending evidence to my thought that the tabletop gaming landscape is split or splitting into two factions where concerning this issue which like all fantasy fiction is a stand-in symbol for attitudes in the community on certain real-life matters if I really had to spell that out (I guess I did, based on some of the reactions I got).

I had put off writing about Orcs as I have about Liches, Elves, Dwarves, and Trolls because to be frank, I always viewed them as cliché and over-used. Embarking on this trip, I had no idea how complex Orcs are. This article was less a tracing of the creation of the modern RPG concept of the Orc rather than the tracing of evidence as to why the concept of the Orc carries such political/emotional baggage as it does. This is especially so for certain demographics of the roleplaying community and the effects it is having on the community thus the subject should be seriously discussed. So, in my mind, the reactions and non-reaction in some quarters were very telling of the general roleplaying community. However, I do cherish the civil feedback and criticisms that I have received so far.

P.S. – I do understand those who did not want the article posted in their groups and on their boards due to the content being “too hot right now”.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

I’ve written another article over at Hubpages. This one I started several months ago in response to a resurgence in the OrcLivesMatter hashtag then as that died down, small arguments here and there erupted about the sociopolitical aspect of Orcs and if they were okay to use in games. After that, Twitter blew up with the “Are Orcs Racist?” question. So, I expanded my research and tried to hone my response to a razor’s edge.

The article is an exploration into the evolution of the Orc as concept from inception to #OrcLivesMatter that strives to answer: are Orcs a racist trope? The answer is much more complicated than you think.

Read it Here.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

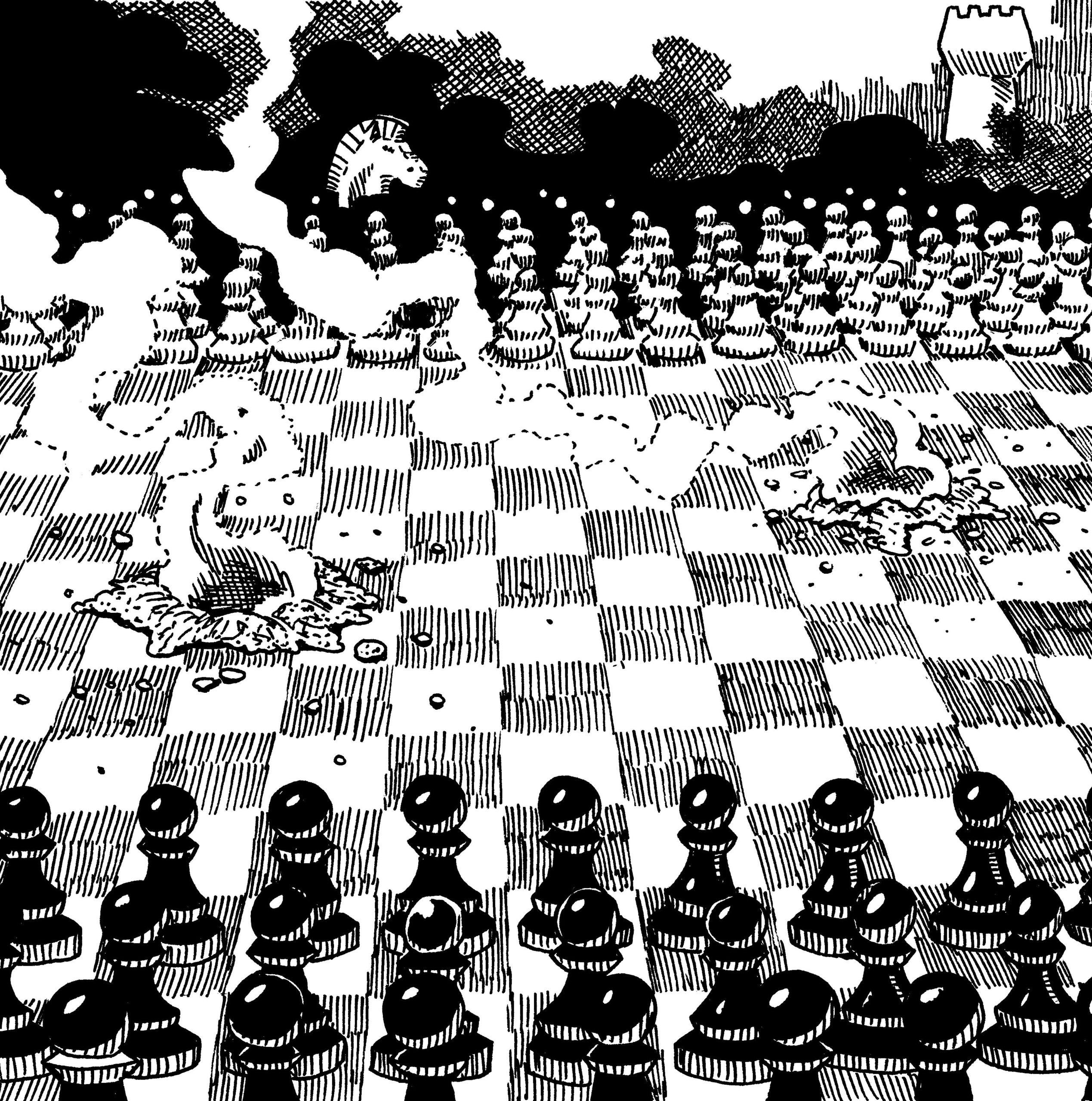

The vista of human-drama and blood-spectacle of a battle-scene enthrall audiences with fury and fire. War operates as a high point of action and emotion in many a heroic epic and countless works of fiction. Battles and war in general often function as the scissor ending character-threads. These of Player Characters (PCs) and Non-Player Characters (NPCs) alike. Sometimes also putting a cap on or violent ending to certain ongoing conflicts. This is war as Set-Piece.

Large-scale battles and war are beyond the scope of most roleplaying games (RPGs), the small more personally focused heroic adventures. In these adventures, battles occur between small groups of adventurers and villains. The typical scope that most RPGs are designed to handle is intimate duels between heroes and monsters. Anything larger in scope is Mass Combat.

When it comes to roleplaying games, the Game-Master (GM) can employ Mass Combat rules. This as a means to create a Set-Piece, which can add action, drama, and structure to a campaign. Set-piece battles can widen the scope of the campaign, especially as a grand finale. A battle is an action and dramatic high point that should come between two lulls in the action. All the while adding to player immersion especially those with inclinations towards strategy. Such set pieces can lend structure to a portion of the campaign as a battle set-piece has a basic structure.

Mass Combat as a term describes a large-scale battle between military units. Military Units being warriors or soldiers gathered into formations and part of a command structure. Whereas a Set-Piece is essentially a spectacle that is also an escalation in danger which serves as an exclamation point in the timeline of a campaign. In common parlance, a Set-Piece describes a “big” scene in a movie. This big scene meant to incur awe in the audience and to escalate and carry along the narrative.

In tabletop roleplaying games (ttRPGs), however, a Set-Piece Battle does not have to inspire awe so much as emphasize danger and define the stakes to the players. Concerning tabletop RPGs, the mechanics of battle are of high importance. For simplicity, I will use the general terms Melee Round and Time Scale in reference to this. Melee Round refers to a slice of time or gameplay where the players’ turns are taken and actions occur. These are typically limited per character and define a discrete slice of in-game time.

Time Scale is a little more general than that. It refers to the scope of time and its dilation between a Melee Round and a round of Mass Combat or its contraction in the other direction. As the scope of Mass Combat is larger as opposed to an individual character’s turn in a melee round. The amount of time a military unit/hero unit takes in a turn is of greater scope. Note that Hero Units refer to units comprised of the PCs and followers if any.

Of course, PCs and other individuals can act quicker than a full unit that is acting in unison. Therefore, PCs’ turns and actions would move more in individual or human scope within the larger action of the battle. This provides more opportunities for the players and the GM to conduct a more exciting game.

The purpose of this article is not to suss out the cause of war or to philosophize about its nature. I will not expound upon its real-life consequences or the immorality of it all. The purpose is to describe how story-tellers and thus Game-Masters can use a battle-scene to improve their game. This increasing enjoyment for all while playing the game. War in the context of this article is not to be construed to be anything more than what is represented in fantasy fiction and miniature wargames.

A Battle shifts perspectives from the epic scale of the full battle using Mass Combat rules to the PCs. PCs are “hero units” on a personal/human scale where normal melee combat rules take over. This allowing the PCs to act in hero mode. An example of this is where a round of mass combat represents 1-minute in time as opposed to 15 seconds per melee round. It is between these two perspectives that the GM must shift to make the most of a battle set-piece.

Shifting back and forth is simple enough. Start with a Mass Combat Round and then move to a single normal Melee Round. Then just alternate until the larger scope is finished and then go back to the normal heroic type game. This works perfectly when the Mass Combat and Melee Round mechanics you use can essentially fit into one another. Like Russian nesting dolls based on their time measurements.

Player characters can act on the mass-combat scale as a military unit moving with it referred to as Hero Units. The GM can allow the hero unit to move as a combat unit during the Mass Combat phase. After that, during the standard melee round then the GM may allow the PCs their full movements on the field as individual heroes. This depending on the mechanics of the game system being used of course.

The reason for this is that even though at the heroic level time moves quicker they get only 1 melee round in between the larger units of game time. Note also whenever the GM deems it fit they can shift focus. Often choosing to focus on the smaller scale of the player characters.

The GM should have a good idea as to how the PCs can alter or otherwise influence the battle. PCs should be able to influence the outcome. The only questions about the battle that matter becomes how much the PCs will influence the battle and how tied to the PC’s personal victories is the outcome of the battle? The GM should already know the answer to that last one; the players are responsible for the first. More questions that definitely matter to the GM are: What are the consequences of victory, of loss?

A GM should come up either with opposing authorities that will attract the ire of the players. This can be done by creating easily identifiable enemy commanders. Or by inserting recurring villains that the players are already familiar with into the upper ranks of the enemy forces. These act as beacons or rather targets for the PCs. This giving them a direction almost immediately or at least as soon as they suss out the enemy commanders.

The GM needs to already have the personal foes of the PCs in places of power. This is even if it is only an honorary or champion position. But it is where the foe holds a strategic position or their loss will cause a fault in opposing morale. Essentially the NPC commanders and champions (and possibly shock troops) are the true main foils to the PCs. Previously introduced foils are valuable in battle set-pieces. As the PCs have some animosity already built towards them they become prominent targets within the enemy force.

The PCs need to not only be able to change the course of history but should be willing to do so in the course of the battle. Perhaps the course of a wider conflict. War, in the context of this article, refers to a series of battles fought strategically. The outcome of each battle has some sort of political, economic, cultural, or raw power value. Any lesser confrontations within this wider war that lacks any of these things are skirmishes. Or are maneuvering for advantage prior to the actual strategic strike. Note that each can be a set-piece unto itself if large and complex enough.

With a full-on war, the GM needs to have an idea of what the impact will be. Whether on the history of the setting/world or the resultant mythology spun around those events later on. Hopefully, this mythology includes tales of the PCs exploits and conduct on the field of battle as well as victories. Much less the mundane spoils of their ventures, however.

Battles are in RPGs as they are in novels and movies. That is a major action sequence that can help to focus the attention of the audience. In this case, players, but they are nothing without some buildup and anticipation on the part of the PCs. The GM needs to build up to such set-piece battles and keep the attention of the players focused. The players should have a clear idea as to where their character stands on the field of battle. Not just regarding loyalties (political, cultural, etc.) but also their personal goals and wherein the command hierarchy they’ll fall.

There should be some “downtime” before the action of the battle. This including some preparation or travel as needed to build some tension using the players’ anticipation to add suspense. They should not be too confident of winning especially when they finally lay eyes on the enemy force. This goes for the reputation, rumors, and personal experiences with the enemy commanders and champions as well.

Using the technique of perspective-shifting as discussed previously the GM can immerse the players in the fight. Especially if they’re responsible for a military unit as commanders. Do not be afraid to throw in an extraneous NPC. This NPC having some backstory and a personality but otherwise the same as the rest of the nameless troop. However, one that the players can interact with and possibly to which assign some emotional value.

The structure of the battle set piece itself allows the battle to rage around the PCs. The melee scope allowing personal level fights on the battlefield. Hopefully against those targets that will make a difference to the outcome using Perspective Dilation. The description given by the GM after a Mass-Combat round is finished should be brief and clear as to the result before going into the Melee Round. This being essentially a PC-eye-level survey of the battlefield around them. Fixing in the mind’s eye the idea that the battle is raging around them as they fight.

Each battle as a set-piece has a certain simple structure that easily translates to game events in a tabletop campaign. As a result, set-piece battles lend their structure to the portion of the game where they occur. This structure consists of three major parts.

The Lead-Up consists of the time when the battle is known to be imminent but has yet to take place. It involves the preparations for the battle, the time used to travel to the battlefield. Also, the time spent trying to track down or corner the enemy. Or even when avoiding them depending on the tactics at play.

This is also the phase where the stakes are made clear if they are not already. To clarify the stakes the GM should ask themselves what will happen if the PCs’ side loses. What will they gain if they win or even does victory or defeat hinge entirely on the PCs’ actions? Is the purpose to win or stall for time or other such goals. The players need to be clued into the answers to these questions.

The Action phase is the battle proper. Conduct this phase as previously described allowing time to dilate and constrict alternatingly for the length of the incident. During this phase, the players have the most influence beside any preparations during the lead-up. All of the major action of and the battle itself occur in this phase. This is the phase that plays most heavily into the mechanics of the system. The end of this phase of a set-piece battle is harder to judge than the end of the lead-up phase though.

The end of the action phase generally happens when the military units are no longer engaged in combat. However, this does not count the lulls in the combat. During lulls in the fighting, GMs may want to revert to the standard Melee Round to better engage the players. Note that a major lull occurs when both sides withdraw to set up camp. Thus allowing them to start up again the next day. This does count as a lull in the action rather than an end of the action phase.

These sorts of actions are counted as extended lulls in the action of the overall set-piece. Not the end of the battle. This even though certain throwbacks to the previous phase can occur here. Especially the pouring over of maps, scouting/spying, and planning for the next day. Though this is all of a smaller scale. It is on the scale of the battlefield. When the action does reach its end the game enters the aftermath stage.

The Aftermath is the result of the battle including all of the dramatic elements. These elements being the loss of friends (remember the extraneous NPC with a backstory?) or companions if a PC should fall. Hardcore roleplaying elements such as questions of morality versus emotion and practicality can arrive into the game narrative. Examples being what to do about the prisoners, what about the wounded both theirs and ours. Are there any refugees to deal with?

How many fighters were routed and from what sides/units? Did they flee into the countryside to become another albeit smaller but more dispersed threat later on? Did the PC’s side win or lose and if either where are the PCs and what actions do they take? Is this just the start of a larger war or the finale of a campaign? What about the families of the dead and wounded? How are the PCs treated after their victory or failure, after a costly victory or an awful slaughter? How terrible was the cost to both or either side and will it lead to diplomatic talks or intricacies as a result?

Whatever the results, both long term and short, the immediate scene should sear itself onto the minds of the players. The scene would be that of the war dead spread across the field and the destruction of the landscape. This vital piece of narrative description can be used as a capper to the action immediately after the fighting. Among this rack and ruin is where the PCs have some breathing room to survey their surroundings. The GM should give players time to react afterward before the storm of questions and logistics fall on their heads.

A battle or for that matter, war, tends to expose the politics at work and/or those that have failed. It also allows all sides to display their military pageantry, their colors, and heraldry. How the generals and commanders conduct battle. Even how the armies are structured exposes a lot about the cultures engaged in the fighting. Particularly when compared/contrasted with each other. War can reveal the true cultural values of a people through raw violent action. This action often contrary to what its representatives may tout. Here the GM can tailor each battle to their campaign world and put more of their imagined cultures on display.

Along with the pomp and politics of war as well as its reflection of the true inner workings of a culture engaged in it war can also have far-reaching consequences. Even a small battle will have some far-reaching and long-lasting effects. The most common of these are stray soldiers including mercenaries. Those who have decided to stick around and survive by pillaging the countryside. Perhaps after deserting their respective outfits or fleeing battle.

Another major and the most visible consequence is the displacement of the locals. Especially true of battles fought in or around a settlement, town, or city. The PCs can be caught up in these peoples’ struggles to just survive. While trying to find another place to settle or just picking up the pieces of their former lives.

Most if not all, would also bear the burden of war forced upon them. This by powers that they have no part or parcel in as well. They would also suffer the loss of material wealth regardless of how meager and some severe permanent physical injury. Refugees and survivors would also bear the mental scars of the war that they had suffered through. Perhaps along with some of the combatants.

The trauma of war can cause a permanent mark on the minds of NPCs and PCs. However, it can also allow them to evolve dramatically such as a rethinking of their alignment (if such a thing exists in the system used). Possibly even causing symptoms of mental illness. Again, if included in the rule-set or even used within the play of the group.

War trauma can be used as a catalyst allowing the player to make sudden modifications to their character. These represent their involvement letting the in-game events dramatically shape the character. Note that small or singular battles often should not go this far. Although characters are free to rethink their stances on fighting on larger scales. Also possibly suffering personal trauma such as the loss of a friend in smaller battles.

A set-piece battle in its very structure involves tension, action, and aftermath providing plenty of roleplaying and roll-playing opportunities. It creates an incident with strategic, dramatic, and consequential levels. It is also a great value to immersion dragging the players along by their characters from anticipation to high-action to realizations or character awakenings in the aftermath.

Battles are also incredibly flexible not only acting as a finale to a campaign but also kick-off a wider conflict. This wider conflict composed of many more such set-pieces. Battles and war will have long-lasting results and consequences that can be explored in an ongoing campaign. This is especially true in a Living Campaign.

Making use of a Mass Combat system within a campaign allows GMs to add spectacle, drama, and exhibit a larger conflict that can work out to an epic scale. Essentially create a big and valuable set-piece. However, a single battle can serve as the finale of an adventure-filled campaign in PC Group centric campaigns. Hopefully resolving most if not all active storylines, snipping loose threads, and ending character arcs in one explosive action sequence.

Battles allow the PCs to accrue reputations and trauma letting the players’ actions to actively sculpt and scar their characters. Using battles as set-pieces is a valuable tool for the well-rounded Gamesmaster. It can help to spice up the game for their group engaging their players on multiple levels at once.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]

Both armies are at a standoff across the field of battle, bright banners flap in the slight breeze, the noon sun glints from the gleaming razor tips of spears and the blades of swords and axes. The dread war-engines vibrate the ground as they’re wheeled into position. Catapults, ballistae, and scorpions are readied. The shouts of the sergeants echo up and down the opposing lines and the frontlines begin advancing towards each other.

Suddenly, choruses of hideous roars tear the skies as a group of dragon-riders surge from the horizon swooping over one side and laying waste to the other. Soldiers desperately try to protect themselves with their tower shields and spears in small bristling testudoes. The earth begins to shake beneath the soldiers’ feet frightening the flanks on both sides loosening their formations. The opposing side, victims of the dragon-riders, opens its middle and a tight cluster of stone golems thunder towards the armored heart of their foe.

As the golems crush their way into the enemy’s ranks, the dragons peel off and strafe the stone monsters with fire barely slowing them down. The warriors of each army crash together in a wave of blood and iron their champions leading. A small squad from the dragon-riders’ side engages the golems with a barrage of acid grenades forged by a mercenary alchemist. Both charging sides meet and the momentum breaks like a wave of blood with the deafening clash of steel and shrieks of dying men. From this blood tide, the champions emerge finally meeting in the middle of the chaos and duel to the death for their respective side and causes.

Fireballs and lightning called down from the heavens by war-wizards at the rear ranks of both armies add to the deafening cacophony. Just then, another smaller cadre of dragons darts into the fray above to engage the enemy dragons. The new comers are less in number but with them comes an enormous blue-black dragon complete with a small crew of riders on his back armed with crossbows, lances, alchemical grenades, and other nasty droppers. The sky darkens with smoke, fire blasts, arrows, and large projectiles as the battlefield spreads from horizon to horizon.

It is total chaos, this battle will be devastating and lay waste the battlefield and most of the surrounding territory which may lay fallow for at least a century after. It’s also cool looking and really gives the Player Characters (PCs) and the Game-Master (GM) multiple opportunities to shine.

The Fantasy Battlefield is a spectacle to behold and its aftermath a tragedy to mourn. It provides the opportunity for the full exercise of strategic thinking, high drama, and innovation. As well as providing potentially spectacular set pieces for the GM. In a fantasy setting, when war occurs it is probable a scene very much like that described above will play out with only the scale varying.

That is because if one side is able to obtain a special and powerful weapon the other side, if it has a competent intelligence network, will find out about it before the fighting. Thus, they will rush to enact countermeasures and try to get their hands on either the same type of weapon or anything else of a similar power level. Of course, this will cause an arms race if the other side is equal in espionage. In addition, if actual world history is any evidence when a weapon or strategic advantage becomes available, it will be used even if just once. In the very least, all the contemporary powers will seek it out vigorously.

There are many reasons to implement large battles and carry out war in a fantasy roleplaying game despite the complications to the Game-Master and the possibility of loss on the Player-Characters’ side of things.

War in game terms is a storyline drawn from a series of confrontations including from the political and not just the combat side involving at least two opposing powers. Within this blob of mass confrontations and tangle of story lines is Mass Combat. Mass Combat is more a technical term to describe mechanics that come into play during instances of combat between at least two large masses of characters. During Mass Combat military units (groups of individuals, typically faceless mook type NPCs) engage in combat where the PCs act as champions or sometimes as complete units unto themselves.

Note that Mass Combat mechanics may not be included in some game systems and those that do will vary greatly in how they function. Therefore, any direct or specific mechanical references will be avoided and more general terms and ideas will be favored in this article.

With the basic mechanical ideas of Mass Combat and Combat Units GMs can begin to construct the spectacle of fantasy warfare. As stated before a battlefield, especially if the battle is a big one, is a remarkable sight when gleaming armies face off not to mention when the fantasy elements come into play adding even more spectacle to the fray. These elements are the true fireworks that really make the set piece unique often involving any one of the Big Four by themselves or in combination.

The Big Four refers to the four major weapons on the field of fantasy warfare: dragons/dragon-riders, golems/constructs, wizards/magic-users, and the undead. Dragons/Dragon-Riders are the super weapon on the field whether they themselves are conscripts, generals, or mounts with a rider or crew. They are a game changer on the field and prompt all sorts of countermeasures and strategies. Golems/Constructs are another super-weapon but one that is most useful against enemy ranks and walls. They are very difficult to obtain and may actually be harder than dragons to get. Golems are more equipment or war-machine than soldier and used thus.

On the other hand, Spell-casters on the field can implement any number of weird and highly powerful strategies using a wide array of magical abilities. These are the easiest of the four to obtain typically serving a mercenary or allied role though they may have their own reasons for joining an army on the march. Spell slinging against the opposite side and summoning forth new and terrible foes for the enemy is their primary battlefield strategy. They can also double as espionage and information gathering agents through their magical abilities. Secondary roles depend on the spell caster’s repertoire such as any healing abilities allowing the mage to run battlefield triage.

The last of the big four are the undead. These often being a part of certain forces popularly considered evil or the full ranks of certain villain types like dark lords, liches, and powerful necromancers. Undead forces typically consist of reanimated corpses or skeletons that can function on the battlefield as warriors and with the ability to take at least simple commands. However, they are often of a weaker type of undead and thus are somewhat weaker than the average soldier is.

The primary strategy of such units is always to overwhelm with numbers and rely on the relentlessness of the undead as they never fatigue or tire. The average leader of one of these units is usually a stronger type of undead though often not of an exceptional level. However, Priests or Paladins (holy warriors) that have certain powers that directly counter undead creatures are a common element that opposes these types of units. They are usually also a part of worlds where these types of creatures run common as a form of universal balance.

Logistics for an undead force are somewhat simplified as they do not get fatigued, they will not starve or die of thirst, and inclement weather has to be severe in order to stall or endanger them. However, in a snowstorm they can freeze solid if they have flesh. Under a hot sun or in dank humid weather, their flesh can rot from their bones. These concerns can make certain types of undead such as zombies less of a threat under specific weather conditions.

Local resistance may be easily directed against a force of undead moving through specific areas. This includes certain religious forces that may have no real interest in the ongoing struggle other than to vanquish the walking blasphemy of the undead. Disease is also a concern when dealing with a diverse army that consists of living and dead forces, as is the predation of the dead upon the living. In addition, those unfortunate enough to be in the way of that force’s path whether allied or not might suffer or die without necessarily being a direct target.

The Big Four are by no means the only exceptional things on the fantasy battlefield. There are also the humanoid powerhouses, which seem on the surface to be more appropriate as powerful soldiery or heavy infantry. This would include such creatures as orcs, trolls, ogres, giants, among others. These may be easier to recruit and maybe to maintain than the Big Four but they would primarily be soldiers and may have certain restrictions imposed on them depending on the setting. Aside from the usual Dark Lord, they may be completely unavailable due to the darkness of their monstrous hearts and even blacker souls (again depending on the setting).

These are not included in the Big Four as they are definitely a remarkable sight but they function much as standard soldiery with perhaps ballistic capability like a hybrid field piece (i.e. giants). Along with the powerhouse-humanoids on the fields of fantasy combat are the unconventional technology and strategies inspired by actual history and that produced by alchemy.