Games-Masters (GM’s) are already like mad scientists modifying their current gaming system often on the fly. This is through either in-play rulings (e.g. building precedence) or directly fabricating rules or guidelines. This is sometimes to patch deficiencies or fill in gaps discovered during play regardless of the potential for unforeseen consequences. Often, GM’s tinker with their current system adding in rules or new additions. However, they are often hesitant to rebuild or mess with the engine of the system.

However, GM’s can achieve some amazing results by doing just such a thing. GM’s can completely rebuild the machinery of a game with only some basic knowledge. Games-Masters can go further than simple modifications stepping into the shoes of a game designer. That is without stepping blindly onto the unsteady ground of game creation from scratch but still achieving something very similar.

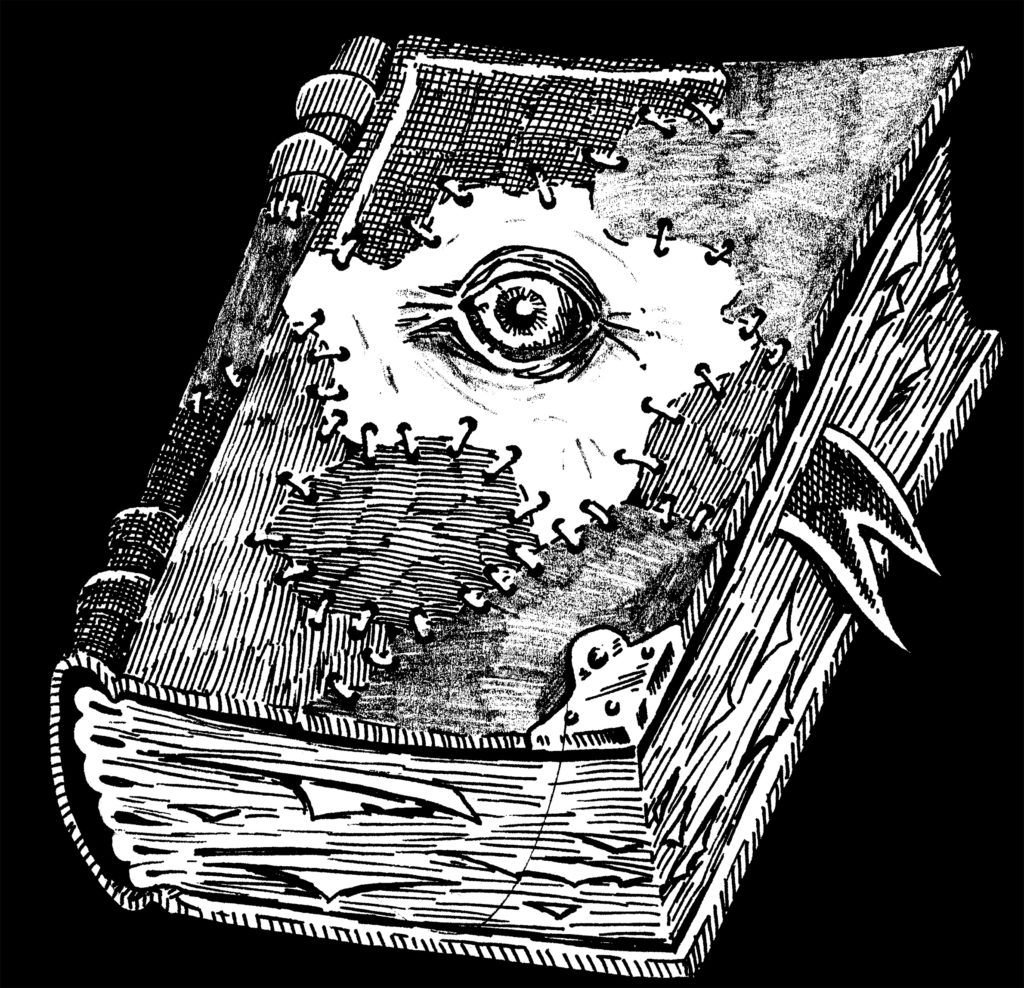

Modifying existing systems is the gateway to creating one’s own full-on tabletop rules-system. However, like Frankenstein’s monster, missteps and using the wrong parts can lead to disaster. All GM’s who have ever run a few games know of the vicious cycle of modifying the modifications. All in service of keeping a campaign limping along.

The Frankengame exists in the realm between the patchwork game and game-creation as a sort of gateway. Here, like Doctor Frankenstein in the graveyard, a Games-Master can get closer to being the creator of their own system. They are starting not from scratch but from the constituent parts dug-up and snatched from sundry and various places. They will know the resulting system more intimately allowing them to avoid the vicious cycle mentioned above. In addition, this process sharpens the mechanical skill of GM’s allowing them to be better able to patch any flaws on the fly.

A Franken-What!?

A Frankengame, like its namesake, is created by taking the operative portions of a game-system referred to here as Modules. Then taking these from multiple other games and slamming them together creating a functional homebrew mash-up. This, in an effort to maximize your enjoyment around the table. This is regardless of whether you or your group are more interested in a more Simulationist or Storytelling gaming mode. Alternately, also useful if you and they enjoy a simplified set of rules or rules-heavy systems.

The newly assembled game should function reasonably well enough to be used as its own standalone tabletop RPG system. Metaphorically similar to the human corpses that contributed to Frankenstein’s monster, you stitch a Frankengame together from the working organs of other games. This is given that all tabletop RPG systems have functional organs that allow them to tick. They share a common anatomy.

Basic RPG Anatomy

A roleplaying game system as a unit is a collection of interacting rules that help to determine the in-game actions of characters. This at least according to Wikipedia. It is also a system of interacting modules, a package of rules and details, each module-package being a subsystem. Modules allow for the construction of in-game items and resolution subsystems. Sometimes they even add to a core resolution system modifying it to some extent based on circumstance.

The common Base Modules of any RPG System are the Combat System, Skill System, the Mystical Engine, and the Object Subsystems. The Mystical Engine being the governing mechanic of the magic & psionic systems as well as any similar such ideas. Object subsystems being the component governing such in-game objects as weapons and armor. The Character Creation system/mechanic can also be included in these modules. This is especially so if there are several different methods presented for players to create characters in the materials.

Base modules are subsystems that handle a specific portion of the game but still have a wide enough reach as to be able to have further subsystems within them depending on their complexity. Note that the more complex the longer it takes to make a rule-call or task-determination. As stated before, these Base Modules handle a limited but still broad aspect of the game. This includes such things as Combat. For example, subdividing combat into such aspects as Vehicular, Barehanded, or even Armed combat although generally it still encompasses these. Similarly, expanding combat with smaller sets of rules or increasing complexity by adding a subsystem to handle one of the different and more specific aspects/scales of combat. At the center of all of these modules and subsystems lay the heart of the RPG, the Core Mechanic.

Core Mechanic

At the heart of the game system from which these modules branch is the Core Mechanic. The Core Mechanic is the principle that all the rest of the system works on. A Core Mechanic is in the simplest terms a formula for conflict resolution. Conflict in this context being an in-game occurrence where an impartial decision is required. Core Mechanics usually rely on a single die roll with certain modifiers added and may even rely on looking up that result on a table or even the number of dice rolled as in a Dice Pool. Most systems wear this on their sleeves so it is easy to get right in there and cut it out so it can share its beat with your homebrewed monstrosity.

Core Mechanic Examples:

- D20 (d20 roll + modifiers vs. a target number)

- Talislanta (d20 roll + Skill or Attribute Rating – Degree of Difficulty; check result to Table)

- World of Darkness (character attributes and skill “pips” together determine the Dice Pool of D10’s vs. a target number)

- Fudge (uses 6-sided plus/minus dice and elevates character attributes rated in an adjective scale (terrible, poor, good, etc.) and lowered or elevated based on the number of pluses and minuses rolled)

A Games-Master/potential Doctor Frankenstein can simply add in or swap certain Base Modules or subsystems with those from another. Although as compared with assembling a completely new system, this counts more as transplantation. However, even mad doctors need some practice. True Frankengames are an actual fusion of at least two other games (hopefully more) and recognizable as apart/different from either of them.

Why Would You Ever Do This!?

Most groups already modify and patch together isolated bits to their favorite systems. Especially when incorporating tweaks, hacks, and divers guidelines/tools from the internet. Taking that farther into Frankengame territory can enrich the Games-Master’s knowledge of tabletop roleplaying systems. But it also builds a custom engine that fits perfectly with their style of play. In addition, the custom engine can answer the needs and wants of the GM and their group. The reasons to begin such an endeavor are manifold.

A Few Reasons to Start a FrankenGame

- To adapt the rule-set to the group’s play-style and wants, or to better suit the theater of the game (its world and/or setting including era).

- In order to reflect the level of involvement in certain aspects of the tabletop RPG hobby, i.e. skewed more to story-telling mechanics or to combat and tactical-based mechanics.

- To push a game towards a more Simulationist version where accuracy rises to the desired level.

- Or to expand the scope or potential of a desired setting or world to include things that another existing system already does, exceeding its current limits.

This last point can be satisfied, and usually is, by simply expanding the rules or transplanting specific chunks or modules. You can use your own invented rules or those borrowed to patch an existing system. However, this births something more of a hybrid system rather than a genuine Frankengame. A true Frankengame pushes even further across that line.

A Frankengame maximizes your vision for your game world, allowing a deeper level of believability (suspension of disbelief). Therefore allowing for deeper emotional ties and freeing you and the players to role-play more within comfortable and familiar bounds. These bounds better fitted to the tastes of the group. However, be warned this is reliant as much on the conduct of players and the GM as a function of system mechanics.

A Step-By-Step Guide to Building a FrankenGame

To begin the process you have to start with the most vital point of any roleplaying game system from which all else circulates – its core mechanic. From here, you can move on to the other points of concern. All other aspects of the game from character creation to all of the modules and subsystems rely on it. They may modify or use it in slightly different ways but all require it to function. There can conceivably be more than a single Core Mechanic. However, rules conflicts and exponentially expanding complexity result from this. Therefore, unless absolutely necessary to your vision it is ill-advised to add more than one.

This does not mean you may use more than 1 type of die in the core mechanic, just that the core mechanic remains the same. An example would be the D20 mechanic of a modified dice roll to meet a set target number. Conceivably, depending on a given subsystem you can use different types of dice or a variant on this basic concept.

What is Necessary?

Next, try to decide which subsystems or modules will be necessary for your game to both function and include those aspects, which you desire. Note that a module can include more than a single subsystem as well as ‘patch rules’ to shore it up. You also have to figure out what modifications are necessary to fit these subsystems to the Core Mechanic. There are 4 or 5 subsystems and modules needed for most RPGs. These are Character Attributes, Skill System, Item Generation, and Combat System, with the Mystic Engine coming in as optional. Most other tertiary systems are a combination of the aforementioned mechanics such as Character Generation and Monster/Creature Generation. These using rules and systematic processes connected to the subsystems to produce an in-game character. Their abilities embedded in or functioning within the applicable game modules.

Torch Proof It

A word of advice in these first few steps, keep in mind how disruptive players might take advantage of the system and its components to break the game. Running some of the still-bleeding rules past a rules-lawyer, min-maxer, or power-gamer can help to mitigate their impact on a fresh Frankengame. Also, stay aware of any gaping holes or gray areas in the rule-set as well. Although you may want to build in some gray areas. This allowing GM rulings to take precedence in certain areas, but gaps should be documented.

Once you have all of the guts for your monster you should begin to organize them. Take note of what parts need to be rewritten or modified to work with the Core Mechanic. Do not forget the other smaller parts as well. You also need to think about how these may interact. Compile a list of each mechanic with notes on how to deal with any inherent flaws. Keep in mind any original bits that you have that will help stitch it together. Drawing a crude diagram of inter-system connections will also help. While dissecting the desired parts from your material RPG-systems, you should throw out any patch-rules that act as connective tissue to other subsystems that you are not taking. However, make sure to keep any for those that you are.

Stitching It All Together

After you have all of the raw material on the table and have a good idea via a list, possibly a diagram of how to put it together, all it takes is stitching it up. After that, make a few test rolls and quick scenario runs to make sure that at least initially it’ll work. Patch-rules serve as your sutures to sew these bits and pieces together.

Rule Patching is a fundamental aspect to creating the Frankengame. It is adding in clauses often based on certain situations to plug up a “hole” in the rules. Alternatively, they can also clear up any unintended gray areas as well. These patches serve not just to correct flaws but are also the connective material between subsystems so that they can function in unison.

Essentially the process for writing a Frankengame is as follows:

- Decide on a core conflict-resolution mechanic (e.g. D20, D6, Fudge, etc.)

- Pick the Core Stats or Character Attributes (the first subsystem) also note that attributes may multiply based on connections to the other subsystems (they are a function of these systems after all).

- Decide on the other necessary subsystems (skill, combat, weapons & armor, social mechanics, etc.)

- Mind interactions across the subsystems as surprises both unpleasant and extraordinary are within these in-between places. The attentions of rules-lawyers focus here typically.

- Compile a list of the modules and subsystems (a connection diagram is helpful).

- Make notes on what modifications and patch rules you will need to apply and where.

It’s Alive!

Creating a Frankengame helps to create a custom system for your group. This has several potential benefits. However, it does take some trial and error even after doing the work of piecing it together. Sometimes it will rise up and be super other times it’ll just strangle you. The main benefit of participating in this activity is learning about the construction of a roleplaying game system on a blood & guts level. In any event, it can give you a firm grounding in the basics of RPG construction.

In addition, exploring a new system with parts that are already familiar can be fun inside of itself. This is especially so when probing for flaws, gray areas, and holes. Even on a dry run of the Franken-system, the group should not be completely lost. The familiar parts may initially give players a steady base from which to explore experiencing genuine surprise when they stumble into new unfamiliar territory. Being the mad scientist type and patching together a Frankengame not to mention hacking established systems apart sharpens your understanding of how RPG systems work. Maybe grafting together a FrankenGame will put you on the road to writing your own original game later on.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]