Characters begin to loot the dusty old room after slaying their foe, some monstrous undead thing. They find the typical loot, some coins, a few gems, and a couple of items. Their first impulse is to appraise the monetary value of the loot and calculate what the split will be. Then they find an old sword hanging on the cobweb-tangled rear wall of the room. When they reach it the Gamesmaster does something that they only half expected. The GM gives the item details that distinguish it from the rest of the loot piquing their collective curiosity.

Giving items a level of detail and a backstory much like a non-player character (NPC) increases that item’s role. The storied item will have a higher position as opposed to other items in the gaming narrative. This technique takes items beyond the role of simple spoils of adventure or a material reward. Note that gaming narrative is different from narratives in the traditional sense. The ‘beats’ of the game tend to follow a perpetual Sine-wave type pattern. High points on the wave being action/drama then dropping back to normalcy. Alternately, they can sink to a low point before the next rise.

Adding details and a history to any item meant for a PC to acquire helps keep certain players on track. This is especially true if the GM hints at the right clues and incidents relating to the item regularly. This can add flavor and detail to the game setting and add some complication to fairly straight forward campaigns. These specially designed items are not just treasure they double as tiny bits of the game world custom packaged for the players to explore.

More than a MacGuffin

To be clear, these are not exclusively MacGuffins. These specially designed items better serve to enrich a campaign. Storied items are not meant to serve as the central focus of a campaign. Nor are they to provide motivation for the group to go on a specific quest. However, they are meant to run the length of the campaign alongside their owners hopefully adding a richness of detail. In a way, storied items ornament a long-term campaign and provide the GM with adventure fodder.

Specially detailed items with a backstory can lead to more adventure hooks. These hooks occurring at the low points of the curve leading to the highs. These items possibly leading to an adventure within an adventure. Similarly, they can lead to side-quests galore branching off or intertwining with the primary campaign focus. It is another thread to weave into the fabric of the game-world. For instance, take a quite common but also much-desired item found in any fantasy campaign, a sword.

A Sword, Any Sword

Any sword, after a morbid fashion, can give (or rather carve) somebody a red smile. However, the true value of unique items with compelling histories and as-of-yet unfulfilled destiny is to Gamesmasters. It is a boon. GMs should try to write up specially designed items. These the players can discover, quest for, win, or loot in the normal course of a campaign. It does not have to be magical or have special powers. However, if that is the carrot onto which your players will bite then by all means.

However, the item needs to be immediately visually (meaning descriptively) interesting. At least to one of the players. This serving as the initial hook. It also does not hurt to try and tailor the item to specific characters. However, always remember to try to attract the players’ attention to it. For an example, let us use a Chinese Dao. It has a long tassel at the pommel and broad, heavy machete-like blade.

There is a sword hanging on the far wall all covered in the same dusty sheet of cobwebs. It appears to be a Dao of a particularly high quality. You can make out the glint of gold, silver, and the glitter of gems. As you look closer, there is a strange faint flickering as of flame. Even from underneath the webs and centuries of sedimentary filth you can see its strange light.

A Hook by Any Other Name

There are a few methods to snag the players using these characterized items. They are very much like those used in writing adventure hooks. You must ask yourself two questions. What type of weapon/item is it and what have the characters been looking for? Additionally, is it something they can pick up and use? However, can the characters also explore its uses (immediate bait). A brief example being a weapon with special features. However, those abilities only make it a more formidable weapon when one learns how to use those features. Of course, this last aspect would rest almost entirely on the system within which you are working.

This brings us to the “Bling.” Bling being the visual details that mark the item as one-of-a-kind. The flashy part of the description. The sole purpose of bling is in attracting the attention of the player(s). Basically, the visual details that tempt them. Start with the main details such as what material(s) make it up. Is this material out-of-the-ordinary or exotic in some way? Are there gems and what kinds, and how are they cut? Are there engravings or inlays? Is the engraving a message of some sort? Can the players read it, or do they need an interpreter? What language is it in? Is it magical script or Elvish? What is the handle wrapping made of? Do the materials, design, or make give hints as to its regional/historical origin?

The Dao blade is of silver and the guard and pommel gold with the engraving of patterns resembling flames. There are characters along the blade inlaid with platinum. They appear to be in an archaic northern dialect. Alternating jade gems, rubies, and deep blue sapphires all cut en cabochon along the guard’s edge sparkle. The tassel that extends from the golden pommel is fire silk and there is a large dark red carbuncle at the base of the blade. This glows with its own flickering flame light. The grip is wrapped in the smooth skin of a metallic blue sea serpent.

Details, Details, Details!

Details construct this special item within the minds of your players. As with the initial appearance of an NPC, the initial description of the item’s general shape and condition affects its perception. Its appearance provides fuel for any perceived or applied “personality”. When in doubt use an engraving bearing a name or saying for an easy addition and telling detail.

The details you use can be battle scars, personal/familial heraldry, makers’ marks, or decorations. These can have attached stories and may play to a certain theme. Visible imperfections will mark the item as unique and may contribute to the backstory. These can be from the original artisan’s hand or even a defect in the base material itself.

The important thing to remember is that these details should mark it out from the rest of the swag. It should be unique compared to that the characters may have come upon up to this point of the game. It should remain at least somewhat unique throughout the campaign. After adding details with at least one marking it unique, a brief history or backstory is necessary to finish it. Certain details should be invented exclusively for the item based on its history.

The blade of the sword shows a deep nick. Apparently, an old battle-wound from an especially powerful blow. Additionally, there is a patch of very pale scales among soft deep-blue scales on the grip. The angler you have asked about the skin on the handle mentions off-handedly an old fisherman’s yarn. It is about a vicious sea-serpent nicknamed ‘Old Scar’ due to the patches here and there on its hide earned from the harpoons of defending sailors.

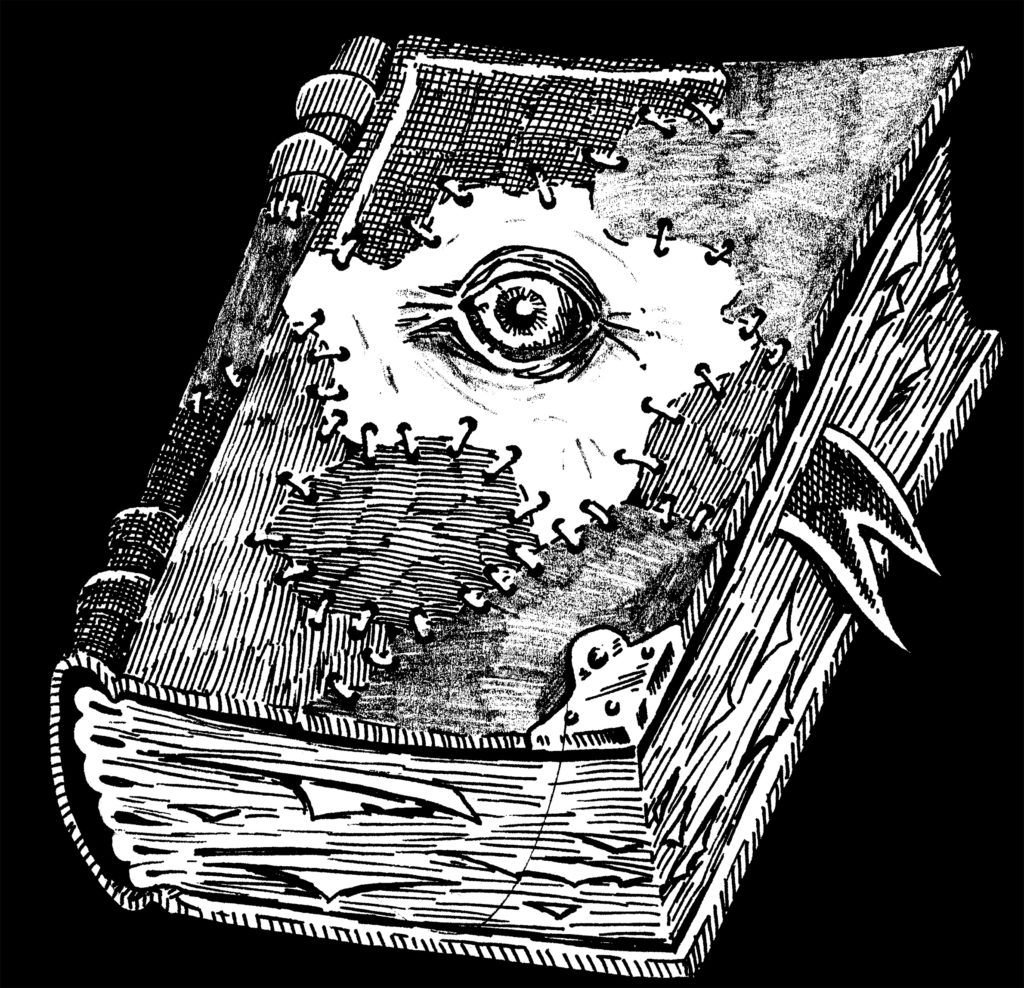

Backstory is Essential

When writing the backstory keep in mind the group resources. You should know what abilities or resources the group possesses to let them probe the backstory of the item. Psychics and spell-casters with certain augury or ESP-effect spells/powers can help by catching tempting glimpses. They can even catch bits of dialogue and other certain clues. Like about who made it, owned it, where it has been, and its unique history. Alternately, if you are trying to hold back certain details these types of abilities may ruin the clue chasing. They may even spill the whole story out all at once. This is when it pays to be subtle. Hone the GM fudging skills using the rules governing these powers to your advantage.

Investigative abilities are certainly suited to engage this type of GM-device. Using science and/or lab skills to gather information in a CSI-like mode is yet another dimension to keep abreast of. In fantasy settings such skills as alchemy would qualify for this mode. However, this is especially so in a modern setting. Do not discount library research either. This allows the GM to create accessories to the item like works that collect lore or document legends. Even antiquarian guides not to mention antiquarian-type characters become more important. These character archetypes are probably the most equipped (besides certain psychics) to delve into such campaign aspects. These types of characters and skills are already, or should be anyway, motivated to participate. They will make it easier for the players to dig into the backstory.

The backstory will consist of a few basic points. Where was it made, who made it, and who was the last owner? Alternately to the latter, who was the most significant character in the item’s history? Pick out the individuals in the backstory that matter the most in-game terms. This can be the craftsman, the original owner, the last owner, or the one who stole it. Only one to two points are necessary to create a rough character outline. Other details can be filled in on the fly. NPCs in the backstory do not require full game stats but need only to communicate impressions to the players. Note that the main characters from the backstory will have names and those names may be recognizable as connected to other legends and stories etc.

NPC Q&A

When conceiving these special items, the GM must ask themselves a few questions to get the creative juices flowing. How recognizable is the item itself? Does it have a reputation? Did the maker/owner of the item have a reputation? Or is there a folktale or story circulating around them and thus the item? Does the item have a name itself? Players and their characters may be asking these questions themselves. Therefore, the GM should have answers ready typically through the mouth of NPCs.

The blade could have been forged somewhere to the south. Where the high-grade silver used for the blade is refined from lead. This is also where the skills necessary to craft such a blade are not rare. There is a village in a remote area of that region rumored to raise the dragon-worms that produce the extremely rare fire-silk, but no one has seen newly spun fire-silk in an age.

A Brief History of Bling

The next step is making the “bling” jive with the history you have written. Turn the details into clues. First, make sure the attached background NPCs, important details, base materials, and general craftwork go together. Make sure that they collectively put the story of the item forward. This does not mean, however, that all the details need to match or correspond in some way. You can also use bling to put forward a telling contradiction between details. Alternately, you can use details as a device putting to the players a puzzle, a paradox to be deciphered. Using the details in this manner can serve to perk up the players’ curiosity. Or help to coax them along the path the item reveals to them.

The characters on the blade say, “Death to the Usurper of the South!” The sea-serpent skin is from an extinct variety of sea serpent. It was known as the Sapphire of the North Seas fished by enterprising fishermen. Additionally, there are characters engraved around the edge of the pommel that are hard to read and badly worn. They mention a name — Master Snake Commander of the… — but the last few characters have worn away.

Backstories & Side-Quests

The backstory the GM creates can lead to a side quest (i.e., away from the main thrust of the campaign). It can run a parallel course, intertwine with the main story usually joining at a certain point. Or can be any combination of the three. Intertwining the backstory of the item with the current campaign direction can keep a wayward player engaged. Doing this by merging their character’s story with it and thus the campaign dragging them along by their curiosity. It can also help to engage players in a concurrent story if the current main plot is not keeping them hooked. At a certain point it can serve to lead them back to the main story at a certain point.

Intersecting points in the main thread with the story of the item can be multiple. Giving a little tidbit of information to the players each time they reach such a story point. Such as while traveling south from a northern frontier the PCs get the related odd tale or a small bit of conversation. Each of these shedding light on specific aspects of the item(s). As the PCs chase down their main goal they will run into the points of the game where the special item figures in.

On your stop-over in the village, the town-drunk regales you with an old story. Its widely known in this region. It is about the young son of a wealthy merchant. The merchant’s riches were said to be held in uncounted smooth-cut gems. Some of which glowed with an inner fire of their very own. A barbaric warlord descended from the mountains with his horsemen and conquered the whole of this region. The merchant’s family slaughtered; their riches pilfered. The son ran to the provinces of the north vowing vengeance upon his return…

A World unto Itself (Sort of)

The backstory of the item can expand upon or add to the campaign world. Just as would a well-constructed NPC but unlike an NPC its details are passive. It requires the players and their characters to investigate them actively. Or have an NPC recognize and communicate what they know about it to the player characters (PCs). Its added flavor if nothing else but it requires the participants to actively engage it. To taste it as it were. This is of course barring any supernatural abilities that may grant the item agency.

These types of specially designed items will add to the game-text for the group. Especially so for the specific player whose character owns it. However, the latter choice may alienate others in the group. Unless you are trying to pit them against each it is probably not the best idea. In this case, tailoring the item to a single character is best. Add in storied items for the rest of the group gradually not all at once.

In fact, it might be useful for the first item to lead to the next and that to another. This lets the GM bait the entire group with each item. Each providing a single piece to a puzzle that begs players to solve it. Or a story that they cannot help but want the conclusion to. Not to mention the items should be useful for the characters in-game. This is outside of the clues and backstory. It is particularly important to never forget this. If it is useless in-game, why would they keep it? Always play to the players’ practical side. However, at the same time use their greed to hook them and their curiosity to propel them.

Players and thus their characters tend to become attached to specially detailed items. Much the same as favorite NPC’s if the backstory and details are just right. The players may even face a hard decision later on in keeping a beloved but mundane item over an upgrade. A rare case of emotional value triumphing over practicality. A well-crafted item can contribute to the overall quality of the game that is if your players are willing to bite.

In Conclusion

Designing a non-MacGuffin item as you would a full-blown NPC has its rewards during gameplay. The item can become a worldbuilding aid as well as evolving into a story point in and of itself. It deepens the game world and can help to engage curious even greedy PCs rewarding them not just materially but with emotional payoff as well.

has any words with them, and they loot every corpse. In fact, loot is just one excuse they use to participate in the slaughter of unfortunate NPCs. What you have on your hands is every GM’s nightmare, a gaggle of Murder Hoboes.

has any words with them, and they loot every corpse. In fact, loot is just one excuse they use to participate in the slaughter of unfortunate NPCs. What you have on your hands is every GM’s nightmare, a gaggle of Murder Hoboes. adventure the expedition begins to fall sick with fever. At first, just a few torchbearers were sick and then a few porters. Eventually almost the entire adventuring party is sick even a few PCs are ill. The danger made apparent before the expedition. However, they assumed it couldn’t be that bad. After all, they had healing magic at their disposal. Now stranded at the center of a monster-infested morass they are bogged down with a sick and dying expedition. In addition, the longer they stay, the more likely more will fall ill. An invisible tiny enemy has brought them to their knees.

adventure the expedition begins to fall sick with fever. At first, just a few torchbearers were sick and then a few porters. Eventually almost the entire adventuring party is sick even a few PCs are ill. The danger made apparent before the expedition. However, they assumed it couldn’t be that bad. After all, they had healing magic at their disposal. Now stranded at the center of a monster-infested morass they are bogged down with a sick and dying expedition. In addition, the longer they stay, the more likely more will fall ill. An invisible tiny enemy has brought them to their knees.