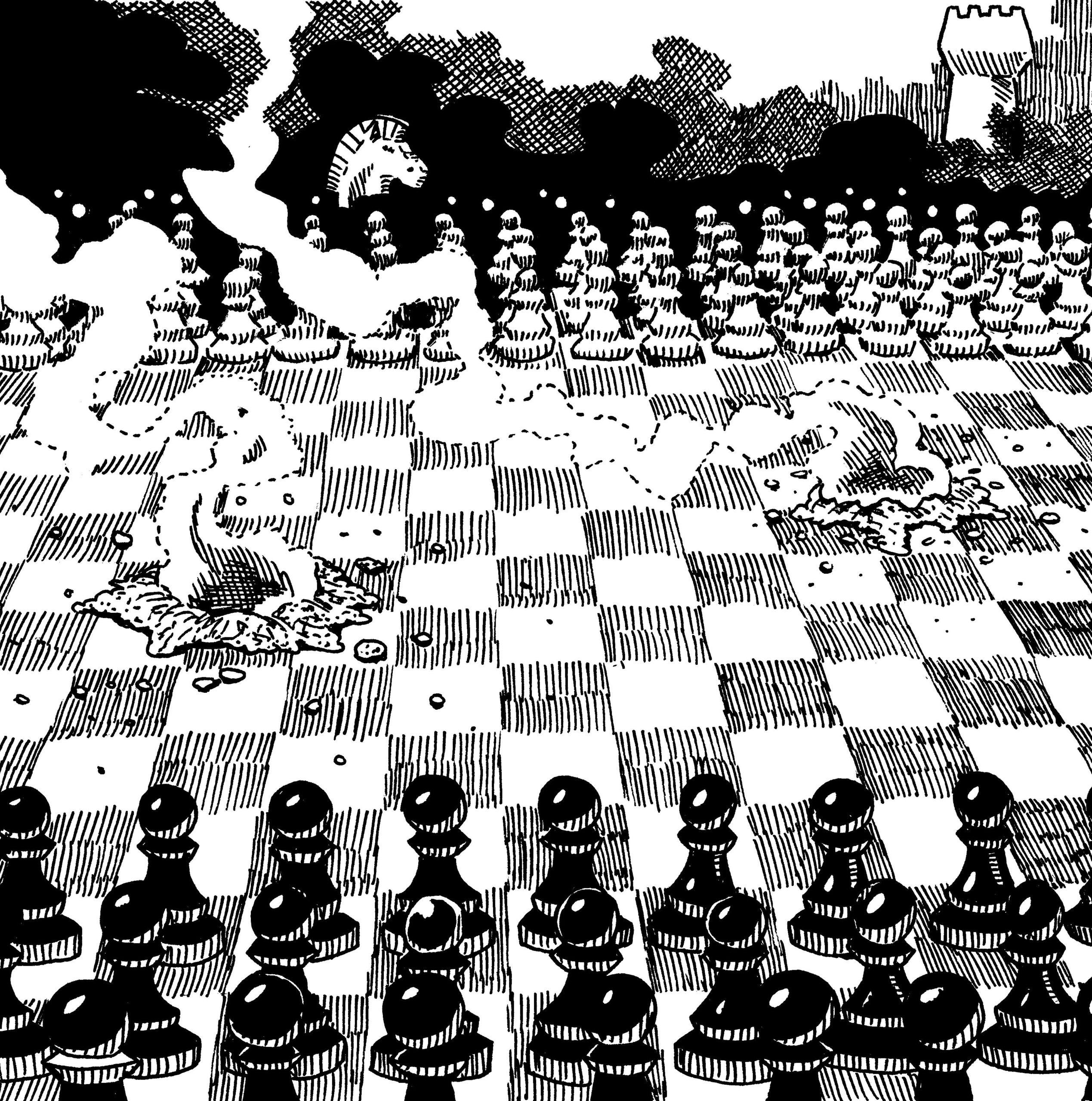

The vista of human-drama and blood-spectacle of a battle-scene enthrall audiences with fury and fire. War operates as a high point of action and emotion in many a heroic epic and countless works of fiction. Battles and war in general often function as the scissor ending character-threads. These of Player Characters (PCs) and Non-Player Characters (NPCs) alike. Sometimes also putting a cap on or violent ending to certain ongoing conflicts. This is war as Set-Piece.

Large-scale battles and war are beyond the scope of most roleplaying games (RPGs), the small more personally focused heroic adventures. In these adventures, battles occur between small groups of adventurers and villains. The typical scope that most RPGs are designed to handle is intimate duels between heroes and monsters. Anything larger in scope is Mass Combat.

Mass Combat

When it comes to roleplaying games, the Game-Master (GM) can employ Mass Combat rules. This as a means to create a Set-Piece, which can add action, drama, and structure to a campaign. Set-piece battles can widen the scope of the campaign, especially as a grand finale. A battle is an action and dramatic high point that should come between two lulls in the action. All the while adding to player immersion especially those with inclinations towards strategy. Such set pieces can lend structure to a portion of the campaign as a battle set-piece has a basic structure.

Mass Combat as a term describes a large-scale battle between military units. Military Units being warriors or soldiers gathered into formations and part of a command structure. Whereas a Set-Piece is essentially a spectacle that is also an escalation in danger which serves as an exclamation point in the timeline of a campaign. In common parlance, a Set-Piece describes a “big” scene in a movie. This big scene meant to incur awe in the audience and to escalate and carry along the narrative.

Time Dilation & Contraction

In tabletop roleplaying games (ttRPGs), however, a Set-Piece Battle does not have to inspire awe so much as emphasize danger and define the stakes to the players. Concerning tabletop RPGs, the mechanics of battle are of high importance. For simplicity, I will use the general terms Melee Round and Time Scale in reference to this. Melee Round refers to a slice of time or gameplay where the players’ turns are taken and actions occur. These are typically limited per character and define a discrete slice of in-game time.

Time Scale is a little more general than that. It refers to the scope of time and its dilation between a Melee Round and a round of Mass Combat or its contraction in the other direction. As the scope of Mass Combat is larger as opposed to an individual character’s turn in a melee round. The amount of time a military unit/hero unit takes in a turn is of greater scope. Note that Hero Units refer to units comprised of the PCs and followers if any.

Of course, PCs and other individuals can act quicker than a full unit that is acting in unison. Therefore, PCs’ turns and actions would move more in individual or human scope within the larger action of the battle. This provides more opportunities for the players and the GM to conduct a more exciting game.

The purpose of this article is not to suss out the cause of war or to philosophize about its nature. I will not expound upon its real-life consequences or the immorality of it all. The purpose is to describe how story-tellers and thus Game-Masters can use a battle-scene to improve their game. This increasing enjoyment for all while playing the game. War in the context of this article is not to be construed to be anything more than what is represented in fantasy fiction and miniature wargames.

Shifting Perspective

A Battle shifts perspectives from the epic scale of the full battle using Mass Combat rules to the PCs. PCs are “hero units” on a personal/human scale where normal melee combat rules take over. This allowing the PCs to act in hero mode. An example of this is where a round of mass combat represents 1-minute in time as opposed to 15 seconds per melee round. It is between these two perspectives that the GM must shift to make the most of a battle set-piece.

Shifting back and forth is simple enough. Start with a Mass Combat Round and then move to a single normal Melee Round. Then just alternate until the larger scope is finished and then go back to the normal heroic type game. This works perfectly when the Mass Combat and Melee Round mechanics you use can essentially fit into one another. Like Russian nesting dolls based on their time measurements.

Player characters can act on the mass-combat scale as a military unit moving with it referred to as Hero Units. The GM can allow the hero unit to move as a combat unit during the Mass Combat phase. After that, during the standard melee round then the GM may allow the PCs their full movements on the field as individual heroes. This depending on the mechanics of the game system being used of course.

The reason for this is that even though at the heroic level time moves quicker they get only 1 melee round in between the larger units of game time. Note also whenever the GM deems it fit they can shift focus. Often choosing to focus on the smaller scale of the player characters.

The Influence of “Heroes”

The GM should have a good idea as to how the PCs can alter or otherwise influence the battle. PCs should be able to influence the outcome. The only questions about the battle that matter becomes how much the PCs will influence the battle and how tied to the PC’s personal victories is the outcome of the battle? The GM should already know the answer to that last one; the players are responsible for the first. More questions that definitely matter to the GM are: What are the consequences of victory, of loss?

A GM should come up either with opposing authorities that will attract the ire of the players. This can be done by creating easily identifiable enemy commanders. Or by inserting recurring villains that the players are already familiar with into the upper ranks of the enemy forces. These act as beacons or rather targets for the PCs. This giving them a direction almost immediately or at least as soon as they suss out the enemy commanders.

The GM needs to already have the personal foes of the PCs in places of power. This is even if it is only an honorary or champion position. But it is where the foe holds a strategic position or their loss will cause a fault in opposing morale. Essentially the NPC commanders and champions (and possibly shock troops) are the true main foils to the PCs. Previously introduced foils are valuable in battle set-pieces. As the PCs have some animosity already built towards them they become prominent targets within the enemy force.

The PCs need to not only be able to change the course of history but should be willing to do so in the course of the battle. Perhaps the course of a wider conflict. War, in the context of this article, refers to a series of battles fought strategically. The outcome of each battle has some sort of political, economic, cultural, or raw power value. Any lesser confrontations within this wider war that lacks any of these things are skirmishes. Or are maneuvering for advantage prior to the actual strategic strike. Note that each can be a set-piece unto itself if large and complex enough.

With a full-on war, the GM needs to have an idea of what the impact will be. Whether on the history of the setting/world or the resultant mythology spun around those events later on. Hopefully, this mythology includes tales of the PCs exploits and conduct on the field of battle as well as victories. Much less the mundane spoils of their ventures, however.

Immersive Action Sequences

Battles are in RPGs as they are in novels and movies. That is a major action sequence that can help to focus the attention of the audience. In this case, players, but they are nothing without some buildup and anticipation on the part of the PCs. The GM needs to build up to such set-piece battles and keep the attention of the players focused. The players should have a clear idea as to where their character stands on the field of battle. Not just regarding loyalties (political, cultural, etc.) but also their personal goals and wherein the command hierarchy they’ll fall.

There should be some “downtime” before the action of the battle. This including some preparation or travel as needed to build some tension using the players’ anticipation to add suspense. They should not be too confident of winning especially when they finally lay eyes on the enemy force. This goes for the reputation, rumors, and personal experiences with the enemy commanders and champions as well.

Using the technique of perspective-shifting as discussed previously the GM can immerse the players in the fight. Especially if they’re responsible for a military unit as commanders. Do not be afraid to throw in an extraneous NPC. This NPC having some backstory and a personality but otherwise the same as the rest of the nameless troop. However, one that the players can interact with and possibly to which assign some emotional value.

The structure of the battle set piece itself allows the battle to rage around the PCs. The melee scope allowing personal level fights on the battlefield. Hopefully against those targets that will make a difference to the outcome using Perspective Dilation. The description given by the GM after a Mass-Combat round is finished should be brief and clear as to the result before going into the Melee Round. This being essentially a PC-eye-level survey of the battlefield around them. Fixing in the mind’s eye the idea that the battle is raging around them as they fight.

The Structure of a Battle

Each battle as a set-piece has a certain simple structure that easily translates to game events in a tabletop campaign. As a result, set-piece battles lend their structure to the portion of the game where they occur. This structure consists of three major parts.

- The Lead-Up – The part leading up to the battle but before the forces are fielded.

- The Action – Starts as the opponents take the field and the battle proper occurring almost entirely on the battlefield. The GM should give a clear description of the battlefield around the PCs when moving from a Mass Combat round into a Melee Round.

- The Aftermath – This occurs after the fighting has stopped or with sieges when the siege ends. Clear winners and losers are not required just a definite end to the current struggle and its action.

The Lead-Up consists of the time when the battle is known to be imminent but has yet to take place. It involves the preparations for the battle, the time used to travel to the battlefield. Also, the time spent trying to track down or corner the enemy. Or even when avoiding them depending on the tactics at play.

This is also the phase where the stakes are made clear if they are not already. To clarify the stakes the GM should ask themselves what will happen if the PCs’ side loses. What will they gain if they win or even does victory or defeat hinge entirely on the PCs’ actions? Is the purpose to win or stall for time or other such goals. The players need to be clued into the answers to these questions.

The Action phase is the battle proper. Conduct this phase as previously described allowing time to dilate and constrict alternatingly for the length of the incident. During this phase, the players have the most influence beside any preparations during the lead-up. All of the major action of and the battle itself occur in this phase. This is the phase that plays most heavily into the mechanics of the system. The end of this phase of a set-piece battle is harder to judge than the end of the lead-up phase though.

The end of the action phase generally happens when the military units are no longer engaged in combat. However, this does not count the lulls in the combat. During lulls in the fighting, GMs may want to revert to the standard Melee Round to better engage the players. Note that a major lull occurs when both sides withdraw to set up camp. Thus allowing them to start up again the next day. This does count as a lull in the action rather than an end of the action phase.

These sorts of actions are counted as extended lulls in the action of the overall set-piece. Not the end of the battle. This even though certain throwbacks to the previous phase can occur here. Especially the pouring over of maps, scouting/spying, and planning for the next day. Though this is all of a smaller scale. It is on the scale of the battlefield. When the action does reach its end the game enters the aftermath stage.

The Aftermath is the result of the battle including all of the dramatic elements. These elements being the loss of friends (remember the extraneous NPC with a backstory?) or companions if a PC should fall. Hardcore roleplaying elements such as questions of morality versus emotion and practicality can arrive into the game narrative. Examples being what to do about the prisoners, what about the wounded both theirs and ours. Are there any refugees to deal with?

How many fighters were routed and from what sides/units? Did they flee into the countryside to become another albeit smaller but more dispersed threat later on? Did the PC’s side win or lose and if either where are the PCs and what actions do they take? Is this just the start of a larger war or the finale of a campaign? What about the families of the dead and wounded? How are the PCs treated after their victory or failure, after a costly victory or an awful slaughter? How terrible was the cost to both or either side and will it lead to diplomatic talks or intricacies as a result?

Whatever the results, both long term and short, the immediate scene should sear itself onto the minds of the players. The scene would be that of the war dead spread across the field and the destruction of the landscape. This vital piece of narrative description can be used as a capper to the action immediately after the fighting. Among this rack and ruin is where the PCs have some breathing room to survey their surroundings. The GM should give players time to react afterward before the storm of questions and logistics fall on their heads.

Some Miscellaneous Fodder

A battle or for that matter, war, tends to expose the politics at work and/or those that have failed. It also allows all sides to display their military pageantry, their colors, and heraldry. How the generals and commanders conduct battle. Even how the armies are structured exposes a lot about the cultures engaged in the fighting. Particularly when compared/contrasted with each other. War can reveal the true cultural values of a people through raw violent action. This action often contrary to what its representatives may tout. Here the GM can tailor each battle to their campaign world and put more of their imagined cultures on display.

Along with the pomp and politics of war as well as its reflection of the true inner workings of a culture engaged in it war can also have far-reaching consequences. Even a small battle will have some far-reaching and long-lasting effects. The most common of these are stray soldiers including mercenaries. Those who have decided to stick around and survive by pillaging the countryside. Perhaps after deserting their respective outfits or fleeing battle.

Another major and the most visible consequence is the displacement of the locals. Especially true of battles fought in or around a settlement, town, or city. The PCs can be caught up in these peoples’ struggles to just survive. While trying to find another place to settle or just picking up the pieces of their former lives.

Most if not all, would also bear the burden of war forced upon them. This by powers that they have no part or parcel in as well. They would also suffer the loss of material wealth regardless of how meager and some severe permanent physical injury. Refugees and survivors would also bear the mental scars of the war that they had suffered through. Perhaps along with some of the combatants.

The trauma of war can cause a permanent mark on the minds of NPCs and PCs. However, it can also allow them to evolve dramatically such as a rethinking of their alignment (if such a thing exists in the system used). Possibly even causing symptoms of mental illness. Again, if included in the rule-set or even used within the play of the group.

War trauma can be used as a catalyst allowing the player to make sudden modifications to their character. These represent their involvement letting the in-game events dramatically shape the character. Note that small or singular battles often should not go this far. Although characters are free to rethink their stances on fighting on larger scales. Also possibly suffering personal trauma such as the loss of a friend in smaller battles.

Summation

A set-piece battle in its very structure involves tension, action, and aftermath providing plenty of roleplaying and roll-playing opportunities. It creates an incident with strategic, dramatic, and consequential levels. It is also a great value to immersion dragging the players along by their characters from anticipation to high-action to realizations or character awakenings in the aftermath.

Battles are also incredibly flexible not only acting as a finale to a campaign but also kick-off a wider conflict. This wider conflict composed of many more such set-pieces. Battles and war will have long-lasting results and consequences that can be explored in an ongoing campaign. This is especially true in a Living Campaign.

Making use of a Mass Combat system within a campaign allows GMs to add spectacle, drama, and exhibit a larger conflict that can work out to an epic scale. Essentially create a big and valuable set-piece. However, a single battle can serve as the finale of an adventure-filled campaign in PC Group centric campaigns. Hopefully resolving most if not all active storylines, snipping loose threads, and ending character arcs in one explosive action sequence.

Battles allow the PCs to accrue reputations and trauma letting the players’ actions to actively sculpt and scar their characters. Using battles as set-pieces is a valuable tool for the well-rounded Gamesmaster. It can help to spice up the game for their group engaging their players on multiple levels at once.

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]