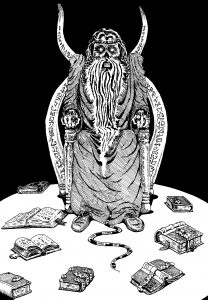

Whether it is at the head of an undead horde or a shadowy figure behind the scenes using monsters  and people like chess pieces the undead wizard known as the lich is adept on and off the field. These undead wizards appear as mostly skeletal with only the scant, mummified remnants of flesh left hanging from their yellowed bones, and in the deep black pits of their perpetually grinning skulls, red pinpoints of hellish light. The lich is a very common archetype in modern fantasy and one of the most recognizable but how far do the roots of the monster actually go?

and people like chess pieces the undead wizard known as the lich is adept on and off the field. These undead wizards appear as mostly skeletal with only the scant, mummified remnants of flesh left hanging from their yellowed bones, and in the deep black pits of their perpetually grinning skulls, red pinpoints of hellish light. The lich is a very common archetype in modern fantasy and one of the most recognizable but how far do the roots of the monster actually go?

The lich is an undead spell-caster that has for the most part deliberately become undead as a bid for immortality able to gather more arcane-knowledge and thus power over time. When they first appeared seemingly out of whole cloth they were undead spell-casters with strange powers, became ideal and grim antagonists, and continue today as antagonists of boss-monster proportions.

[A] mage or cleric so thirsty for immortality as to try to cheat death, and already powerful at magic. [Greenwood, Ed. 1988. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Forgotten Realms, The Lords of Darkness. TSR, Inc. 2]

A lich is an undead creature therefore; our concerns lie first with the condition of undeath and the meaning of ‘undead creature’. First off, undead creatures were formerly living and thus have had a “first death” rising from the grave weirder and more powerful.

Undead creatures are dead bodies animated often by an outside force after the soul of the dead being has since flown from the bones. This force, often malicious, oft defined as demonic and occasionally elemental replaces the soul as the animating force and/or mind. This force typically alters the corpse in significant and grotesque ways to adapt the newly formed creature to its new (un)life as a creature of the night. In the case of Liches, this force is magic rather than a demonic spirit though perhaps still elemental. However, their actual soul has been captured in a special object called a Phylactery. The transformation of the body to the being of a lich is the death of the mage and the rotting of the corpse leaving only that necessary to contain the animating force. The once living visage reduced to the bones with maybe some withered, leather-tough tatters of flesh to hold the joints together.

The urge for immortality is so strong in some powerful mages and magic-user/clerics that they aspire to lichdom, despite its horrible physical side effects and the usual loss of friends and living companionship. Lichdom must be prepared for in life; no true lich ever is known to have come about “naturally”. [Greenwood. pg.73]

The term and the creature fused together in the pulp fiction of the early 20th century. For the most part the term was used as an archaism. An archaism is a deliberate imitation of old-fashioned language in order to stress a certain time-frame or to enhance atmosphere. Similar archaisms were revived and sometimes redefined by the popular imagination in that fertile ground known as American Pulp Fiction, namely in the fantasy and horror genres of weird fiction. Masters and innovators of modern archaisms as literary device included such well-known names as H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith.

The etymology of the term Lich, plural Liches, is straightforward. Its roots lie in the Old English word for ‘corpse’, not a monster or evil spirit, just a dead body: “A corpse (Old English lic).” [Rockwood, Camilla ed. 2009. Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase & Fable 18th Edition. Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd. 781] Though archaic its original use lingers in certain usages such as ‘lich gate’ and a few others.

“Lich gate or lych gate The covered entrance to churchyards intended to afford shelter to the coffin and mourners while awaiting the clergyman who is to conduct the cortége into church.”

“Lich wake or lyke wake The funeral feast or the waking of a corpse, i.e. watching it all night.”

“Lychway or lickway A trackway, especially in a remote upland area, along which corpses were borne for burial in a distant churchyard.” [Rockwood. 781]

The modern fantasy trope of the Lich may have indeed started with the term itself.

Pulp Fiction where most modern fantasy archetypes were, if not born, then mantled with their modern guises, the lich is no exception. However, in regards to the lich this lineage begins with the appearance of the term “lich” in weird stories beginning in the 19th century with Ambrose Bierce at the very beginning of the weird genre of fiction.

One of the earliest appearances in fiction of the word occurs in Ambrose Bierce’s story the Death of Halpin Frayser. In fact, the fictional quote that precedes the story is the earliest part to mention our undead subject.

For by death is wrought greater change than hath been shown. Whereas in general the spirit that removed cometh back upon occasion, and is sometimes seen of those in flesh (appearing in the form of the body it bore) yet it hath happened that the veritable body without the spirit hath walked. And it is attested of those encountering who have lived to speak thereon that a lich so raised up hath no natural affection, nor remembrance thereof, but only hate. Also, it is known that some spirits which in life were benign become by death evil altogether. [Hopkins, Ernest Jerome ed. 1970. The Complete Short Stories of Ambrose Bierce. University of Nebraska Press. The Death of Halpin Frayser]

Soon after the term was adopted by one of the three musketeers of weird fiction, Clark Ashton Smith. His connection to Bierce being that: “At fifteen, [Clark Ashton Smith] became likewise infatuated with [the poetry] of George Sterling. Sterling (1869-1926) had moved from his native New York State to California in 1891 and had become a protégé of Ambrose Bierce – “bitter Bierce,” the misanthropic writer, poet, journalist, and satirist[.]” [De Camp, L.Sprague. 1976. Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy. Arkham House . Sauk City, Wisconsin. 199]

Bierce himself was quite aware of the young writer. “In 1912, Ambrose Bierce wrote to a western magazine, warning that, while Smith was a very promising young poet, this premature publicity and exaggerated praise might be bad for him and lead to an equally exaggerated reaction against him.” [De Camp. 201]

Eventually through his use of the word and his close connections via written correspondence, his contemporaries, Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft, began to use the word as well. However, Smith used the term more often to describe an animated corpse than an undead wizard. This is around 1926 and the lich is still a little strange.

But on its heels, ere the sunset faded, there came a second apparition, striding with incredible strides, and halting when it loomed almost upon me in the red twilight – the monstrous mummy of some ancient king, still crowned with untarnished gold, but turning to my gaze a visage that more than time or the worm had wasted. Broken swathings flapped about the skeleton legs, and above the crown that was set with sapphires and balas-rubies, a black something swayed and nodded horribly; but, for an instant, I did not dream what it was. Then, in its middle, two oblique and scarlet eyes opened and glowed like hellish coals, and two ophidian fangs glittered in an ape-like mouth. A squat, furless, shapeless head on a neck of disproportionate extent leaned unspeakably down and whispered in the mummy’s ear. Then, with one stride, the titanic lich took half the distance between us, and from out the folds of the tattered sere-cloth a gaunt arm arose, and fleshless, taloned fingers laden with glowering gems, reached out and fumbled for my throat… [Connors, Scott ed. 2006. The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith Volume One. Night Shade Books. San Francisco. The Abominations of Yondo. 7-8]

In his 1932 story The Empire of the Necromancers, the lich has lost the weird belly-monster and taken the basic form of an animated corpse. “After a while, in the grey waste, they found the remnants of another horse and rider, which the jackals had spared and the sun had dried to the leanness of old mummies. They also raised up from death; and Mmatmuor bestrode the withered charger; and the two magicians rode on in state, like errant emperors, with a lich and a skeleton to attend them.” [Connors, Scott ed. 2007. A Vintage from Atlantis: The Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith Volume Three. Night Shade Books. San Francisco. The Empire of the Necromancers . 194] And “All that night , and during the blood-dark day that followed, by wavering torches or the light of the failing sun, an endless army of plague-eaten liches, of tattered skeletons, poured in a ghastly torrent through the streets of Yethlyreom and along the palace-hall where Hestaiyon stood guard above the slain necromancers.” [Connors. A Vintage from Atlantis. 199]

Eventually Robert E. Howard resourced the lich for his mystical two-fisted adventure tale Skull-Face in 1929.

I shuddered. Kathulos laughed wildly again. His fingers began to drum his chair arms and his face gleamed with the unnatural light once more. The red visions had begun to seethe in his skull again.

“Under the green seas they lie, the ancient masters, in their lacquered cases, dead as men reckon death, but only sleeping. Sleeping through the long ages as hours, awaiting the day of awakening! The old masters, the wise men, who foresaw the day when the sea would gulp the land, and who made ready. Made ready that they might rise again in the barbaric days to come. As did I. Sleeping they lie, ancient kings and grim wizards, who died as men die, before Atlantis sank. Who, sleeping, sank with her but who shall arise again!” [Howard, Robert E. 1974. Skull-Face Omnibus. Neville Spearman, London.]

Of course, Lovecraft followed suit in his The Thing on the Doorstep originally published in 1937. “He must be cremated – he who was not Edward Derby when I shot him. I shall go mad if he is not, for I may be the next. But my will is not weak – and I shall not let it be undermined by the terrors I know are seething around it. One life – Ephraim, Asenath, and Edward – who now? I will not be driven out of my body … I will not change souls with that bullet-ridden lich in the madhouse!” [Derleth, August ed. 1963. The Dunwich Horror and Others. Arkham House Publishers, Inc. Sauk City, Wisconsin. The Thing on the Doorstep. 300]

Though Lovecraft used the term lich to mean the body of the possessed he is probably trying to get the idea through to the reader that the original inhabiting personality is gone essentially slain by the thing that now occupies the flesh. Although within the story, it does concern a sorceress who cheats death by taking possession of others’ bodies even able to drive her former corpse around very similar to the current incarnation of the lich.

These three tales forever merged in the minds of pulp readers the image of the skeletal corpse with the idea of a powerful undying sorcerer. From there the word seeped into the lexicon of fantasy writers but the archetype was not yet quite complete.

The basic idea of the lich naturally filtered to the latter day pulp writers, in particular one Gardner Fox and his Conan-Kull pastiche Kothar. In his 1969 novel Kothar: Barbarian Swordsman a lich appears that will serve as the basis for all future undead wizards in the popular mind.

He turned and stared back into the dark tomb and saw the dead thing standing in the darkness, rotted and ugly in its cerements. […] It was just a corpse, a corpse that walked and spoke and seemed to be alive.

“Who are you?” Kothar growled.

“My name is Afgorkon, long and long ago.”

Kothar scowled. Afgorkon? Surely he had heard Queen Elfa speak of Afgorkon who had been a mighty magician fifty thousand years ago. He tried to think, but could not, being held in thrall by the black, empty eyeholes of the dead thing standing before him, bent and brown and old.

[…]

The lich turned and moved with those strangely thumping footsteps across the tomb. Its rotted hands moved and its withered tongue clacked, and sounds issued from the throat that was little more than bones. The words it spoke reverberated throughout the cairn, they brought down tiny showers of dirt from the root-pierced ceiling, they made the death-slab shake.

Yet they also opened an invisible door and caused a pallid glimmer by which Kothar could see, past the burial garments which still encased Afgorkon, an opening door and a chamber where lay a sword in a scabbard chained to a great leather belt on top of two chests heavy with jewels and golden coins of a kind no man had looked upon for half a million years.” [Fox, Gardner, F. 2016. The First Kothar the Barbarian Megapack. Wildside Press LLC. Kothar: Barbarian Swordsman]

Fox was definitely inspired by Howard’s Conan the Barbarian as Kothar the Barbarian is near identical though apparently less intelligent and with the sexual content of the stories turned up. On a related note The Cat and the Skull, a story written for Weird Tales by Robert E. Howard around 1928 saw print in 1967 in the King Kull lancer paperback.

The face of the man was a bare white skull, in whose eye sockets flamed livid fire!

“Thulsa Doom!”

[…]

“Aye, Thulsa Doom, fools!” the voice echoed cavernously and hollowly.

“The greatest of all wizards and your eternal foe, Kull of Atlantis. […]”

[…]Brule charged with the silent ferocity of a tiger, his curved sword gleaming. And like a gleam of light it flashed into the ribs of Thulsa Doom, piercing him through and through so that the point stood out between his shoulders.

Brule regained his blade[.] Not a drop of blood oozed from the wound which in a living man had been mortal. The skull-faced one laughed.

“Ages ago I died as men die!” he taunted. “Nay, I shall pass to some other sphere when my time comes, not before. I bleed not for my veins are empty and I feel only a slight coldness which shall pass when the wound closes, as it is even now closing. Stand back, fool, your master goes but he shall come again to you and you shall scream and shrivel and die in that coming! Kull, I salute you!” [Louinet, Patrice ed. 2006. Kull Exile of Atlantis. Ballantine Books, New York. The Cat and the Skull]

Most importantly however, Gardner’s novel was read by Gary Gygax whom used the lich in that story as his template for the monster in his game Dungeons & Dragons.

“While a few of the critters in questions are purely products of my own imagination–carrion crawler, gelatinous cube, roper for instance–there were many sources of inspiration for the majority of the monsters, and I will name a few: […] Lich: Right on in regards to Gardner Fox. Gar and his wife Linda were friends of mine.” [Gygax, Gary. 2007. EnWorld.Org. Forum Post]

We have finally arrived at the Archetypical Lich. The Undead Magic-User or Priest that willingly underwent the lethal mystical transformation into an undead monster has taken its modern form. “Preparation for lichdom occurs while the figure is still alive and must be completed before his first “death”.” [Mohan, Kim ed. 1981. Lenard Lakofka auth. 1979. Best of Dragon Vol.II. Blueprint for a lIch.] After they have successfully undergone this process, the wizard’s soul has been captured within the Phylactery singly the most valuable item in any lich’s amassed treasury no matter how vast.

The word Phylactery is defined in the dictionary as an amulet but also refers to devices of orthodox Jewish prayer. In that respect, phylactery refers to two small leather boxes containing slips of vellum on which are written portions of Mosaic Law. One is worn on the head and the other on the left arm in token of the duty to obey religious law. Strangely, the lich’s phylactery reflects these ideas, as it is a magic amulet containing its living soul, which the lich must protect. If it is destroyed, so is the lich.

The phylactery may take any form – it may be a pendant, gauntlet, scepter, helm, crown, ring, or even a lump of stone. It must be of inorganic material, must be solid and of high-quality workmanship if man-made, and cannot be an item having other spells or magical properties on or in it. It may be decorated or carved in any way desired for distinction. [Greenwood. pg.74]

The idea of it being a mystical container for the soul of a sorcerer is similar to the character of Koschei the Deathless from Russian mythology. The basic idea found in mythology of a powerful wizard, evil king, troll, or other monster being able to hide its heart or soul somewhere else preventing them from being slain is an old one.

Unlike most undead Liches retain all of their knowledge from life and have an eternity to become masters at anything they choose. Therefore, the archetypical lich is uber-powerful or in the very least has extremely refined skills often of the arcane variety, the perfect villain to set against a group of rowdy adventure seekers.

With the lich as a villain, there are a couple of things to ask about the fundamentals of their character stemming from a few problems posed by their immortality and especially the type of immortality that they have achieved. The Lich is an undead creature, an animate corpse with magic power, created by imprisoning its soul in a phylactery. In some circles, the soul is believed to be the seat of intelligence (and indeed, in certain game systems it may very well be). Does this mean that in actuality, the wizard has imprisoned himself in a psychic prison (the Phylactery) and the creature that is the corpse is just a mockery with a black (or grey) soul of pure magical force?

As they are sentient, do they suffer the emotional consequences of being left behind by their world and the familiar? Is that why they occupy themselves sometimes for decades or even centuries perusing their labyrinthine libraries burying their ruined faces in rotting tomes as their world disintegrates around them? Would this render them insane, depressed, delusionally out-of-touch, or erratic in their behavior? Do they desire some connection any connection to other beings even if it is negative, perhaps violence is the only way they can relate to others. I suppose that individual Game-Masters and their Lich characters should answer these questions on a case-by-case basis those questions best left for them.

In summary, the modern archetypical lich as an undead magic-user that has trapped their own soul  within a phylactery was born of an archaism utilized by pulp authors in their weird tales. They were then borrowed and honed into their final wretched form by Gary Gygax and continue to appear in very similar if not identical forms across media such as the lich in Adventure Time, World of Warcraft: Wrath of the Lich King, and in a slightly altered version in the guise of the Night King in Game of Thrones.

within a phylactery was born of an archaism utilized by pulp authors in their weird tales. They were then borrowed and honed into their final wretched form by Gary Gygax and continue to appear in very similar if not identical forms across media such as the lich in Adventure Time, World of Warcraft: Wrath of the Lich King, and in a slightly altered version in the guise of the Night King in Game of Thrones.

“I know what the dead know.” – Afgorkon [Fox. 22]

As an afterword, I am aware that Frank Belknap Long also used the term lich in his 1924 Weird Tales pulp story The Desert Lich. However, it has very little substance of the Lich in anything else besides its title. “The Desert Lich has an Arabic setting, but is a non-supernatural conte cruel in which a man who had sold an unfaithful wife is forced to lie in a sarcophagus with her corpse.” [Joshi, S.T. 2004. The Evolution of the Weird Tale. Hippocampus Press. New York, New York. 99]

[do_widget id=”cool_tag_cloud-4″ title=false]